People and social interaction, not technology, is the key to the future of cities

Smart city afficianado’s are agog at the prospects that the Internet of Things will create vast new markets for technology that will disrupt and displace cities. Color us skeptical; our experience with technology so far–and its been rapid and sweeping–is that it has accentuated the advantages of urban living and made cities more vital and important. From the standpoint of urban living, one should regard “IoT” as “the irrelevance of thingies.”

It’s been more than two decades since Frances Cairncross published his book “The Death of Distance” that prophesied that the advance of computing and communication technologies would eliminate the importance of “being there” and erase the need to live in expensive, congested cities. (It goes down, along with Francis Fukuyama’s “End of History” and Kevin Hassett’s “Dow 36,000” as one of the demonstrably least accurate book titles of that decade.)

Back in the 1990s, when the Internet was new, there was a widely repeated and widely accepted view of the effect of technology on cities and residential location. The idea was “the death of distance”–that thanks to the Internet and overnight shipping services and mobile communications, we could all simply decamp to our preferred bucolic hamlets or scenic mountaintops or beaches, and virtually phone it in.

And these predictions were made in an era of dial-up modems, analog cell-phones (the smart phone hadn’t been invented, and while Amazon was still making most of its money cannibalizing bookstore sales). We were all going to become “lone-eagles”, tipping the balance of power away from cities and heralding a new age of rural economic development. Here’s a typical take from 1996, courtesy of the Spokane Spokesman Review:

Freed from urban office buildings by faxes, modems and express mail, lone eagles are seen by economic development experts as a new key to bolstering local economies, including those of rural areas that have been stagnant for much of the century.

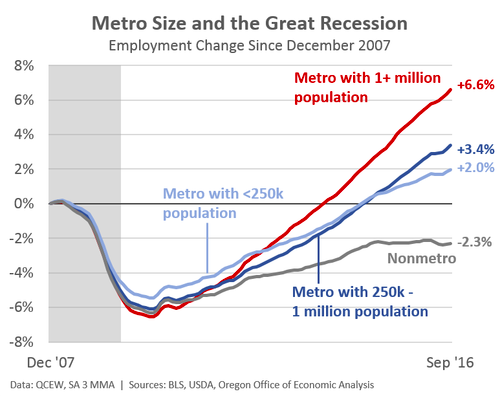

Faxes? How quaint. Since then, of course we’ve added gigabit Internet and essentially free web conferencing and a wealth of disruptive apps. But despite steady improvements in technology, pervasive deployment and steadily declining costs, none of these things have come to pass. If anything, economic activity has become even more concentrated. Collectively, a decade after the Great Recession, the nation’s non-metropolitan areas have yet to recover to the level of employment they experienced in 2008; meanwhile metro areas, especially large ones with vibrant urban cores, are flourishing.

The economic data put the lie to the claim that cities are obsolete. One of our favorite charts from Oregon economist Josh Lehner points point that larger metropolitan areas have outstripped smaller ones and rural areas have continued to decline in this tech-based era.

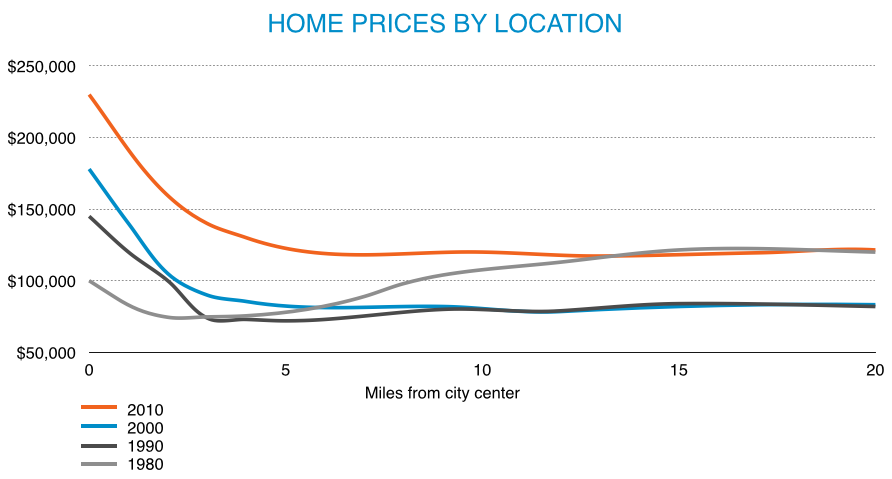

But what’s more than this is the growing premium that people pay to live in center of cities. Economists call this the urban rent gradient: the price of housing is more expensive in the center of regions, which are generally the most convenient and accessible to jobs, amenities and services. Over the past two decades, the urban rent gradient has steadily grown steeper: people now may more to live in the center of cities than ever before.

The importance of this trends was identified by University of Chicago economist Robert Lucas writing in the late 1980s. His words are even truer today that they were then:

If we postulate only the usual list of economic forces, cities should fly apart. The theory of production contains nothing to hold a city together. A city is simply a collection of factors of production – capital, people and land – and land is always far cheaper outside cities than inside. Why don’t capital and people move outside, combining themselves with cheaper land and thereby increasing profits? . . . What can people be paying Manhattan or downtown Chicago rents for, if not for being near other people?

The expanding power and falling price of computation and electronic communication has made these things not more relevant, but less relevant to location decisions. Because you can get essentially all these things anywhere, they make no difference to where you locate. What’s ubiquitous is is irrelevant to location decisions.

The growing ease and low cost of communication has, paradoxically made everything else relatively more important in location decisions. What’s scarce is time and the opportunities for face-to-face interaction.

Both in production and consumption, proximity are more highly valued now than ever. Economic activity is increasingly concentrating in a few large cities, because they are so adept at quickly creating new ideas by exploiting the relative ease of assembling highly productive teams of smart people. Cities too offer unparalleled sets of consumption choices close at hand. From street food, to live music, to art and events, being in a big city gives you more to choose from, more conveniently located and cheaper than you can get it anywhere else. Plus cities let you stumble on the fun: discovering things and experiences that you didn’t even know existed.

The “death of distance” illusion is being repeated today with similar claims about the impending disruption from “the Internet of Things.” On a municipal scale this manifests with the cacophony of visions for tech-driven smart cities. Supposedly attaching sensors to everything from cars, to streetlights, to water meters is going to produce a quantum leap in city efficiency.

Far from provoking a shift to the suburbs and a decline of cities, the advent of improved computer and communication technologies has help accelerate the revival of urban work and living. In recent comments to the Urban Land Institute’s European meeting in the Netherlands, Harvard Economist Ed Glaeser explains.

“So why didn’t computers kill cities?” Glaeser asks. It’s a fair question: remote working has never been more possible, and productivity has never been higher. So why are more people flocking to urban areas than ever? “Cities are about exchanging ideas,” he says. The proximity of people to other people sparks ideas in a way that is impossible in remote areas.

As Philip Longman wrote at Politico a few years back:

. . . in the centers of tech innovation, . . . the trend has been toward even greater geographic concentration, as Silicon Valley venture capital firms such as the storied Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers have set up offices in downtown San Francisco, closer to the action. Apparently, there is no app that will bridge the gap. To seal the deal, you must be in the room, literally, just like some tycoon from the age of the robber barons.

As technology becomes cheaper and more commonplace, it ceases to be the determining factor in shaping the location of economic activity. All the other attributes of place, especially human capital, social interaction and quality of life–the kinds of things that are hardest to mimic or replace with technology, become even more valuable. To be sure, the Internet of Things may disrupt some industries and promote some greater efficiency, but the arc of change is moving inexorably to the city.