To some observers, planners’ promises that more housing supply will push down prices don’t seem to be working. In recent years, rents have jumped substantially, and it doesn’t seem like market forces are working to ameliorate this trend. Although the historical evidence linking faster housing construction growth and slower housing price growth is quite strong, it can often be difficult to convince people who don’t spend lots of time with regression printouts—that is, most people—of the relationship.

But there is good news on that front: rents in Seattle, Denver, and Washington, DC appear to be easing significantly. In what a local business paper describes as an “alarming deterioration”—though renters probably have different words for it—the average Seattle rent fell by $59 in the last quarter of 2015, following a long period of rapid increases. Not coincidentally, vacancies also increased by a full percentage point. The Puget Sound Business Journal reports that landlords have reason to worry that things aren’t going to get any “better” for them: another 21,600 units of housing under construction should hold down rent growth into the coming year, too.

It’s the same story in Denver. After a surge of new construction, vacancy rates shot up from 5 to 6.8 percent in the fourth quarter of 2015. As a result, median rents—which had grown by nearly $250 a month from the first to the third quarter of the year—fell by $7 in the last quarter.

And in Washington, DC, real estate firm Yardi Matrix says that rent increases have been held in check for the past year by the large number of new apartments coming online—and expects the same pattern to hold for 2016.

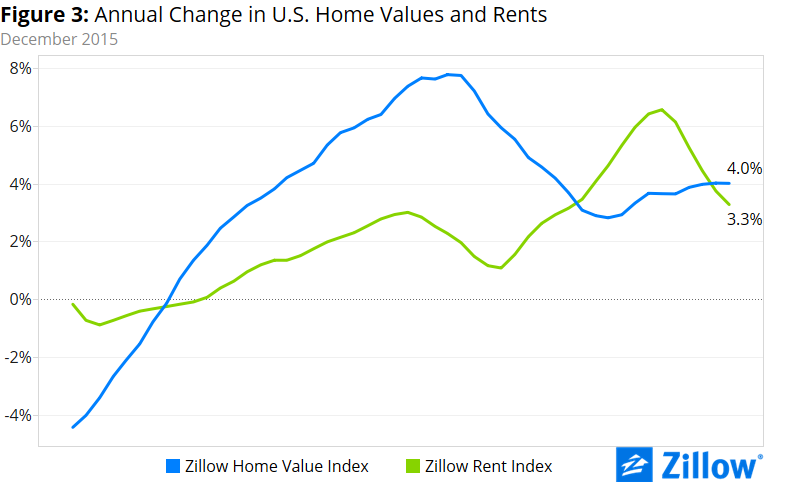

In fact, this is a national story. Overall apartment construction, which has struggled to keep up with the growing demand for rental units, surged by over 20 percent in 2015—and rent growth slowed to 3.3 percent in December, and is projected by Zillow to fall to 1.1 percent by the end of 2016.

The examples of Seattle and Denver ought to be a model for other cities seeing a surge of central-city housing demand. There is an alternative to the never-ending upward prices of regions like the San Francisco Bay Area, and it involves allowing housing supply to meet demand.

A key issue here is what you might call the “temporal mismatch” between demand and supply. Demand can change very quickly for a variety of reasons: growth in the local economy, popularity of a particular neighborhood, the unattractiveness or unaffordability of homeownership, demographic changes, and so on. But supply changes slowly, because it takes time for developers to recognize that demand has changed—and then it takes time to design, permit, and build new capacity. This is especially true in places with restrictive land use laws. But when supply eventually responds—as it has in several of these markets—rent increases moderate, and in some cases rents even decline.

There are some other important lessons if you dig into the numbers a bit. As the Denver Post points out, the vast majority of new construction in that city, as elsewhere, has been at the high end of the market. As a result, vacancy rates are highest in more expensive neighborhoods. In part, this is just the nature of new construction: it generally costs much more money to build new than to maintain an older building, and so new construction will target relatively higher price points. In addition, the long buildup of higher-end demand in central cities gave developers a strong incentive to build to that market. As higher-end demand is better met and rents stabilize or fall, it may become more profitable for developers to target slightly less affluent parts of the market.

But this also shows the importance of allowing, and encouraging, low-construction-cost “missing middle” housing over broad swaths of a city. That’s the kind of development that’s most likely to be able to meet the housing needs of moderate-income households, without a subsidy—if not right away, then after it has downfiltered a bit.

But already, the power of increasing housing supply to halt rapidly rising rents is playing out in real time in cities across the country. That’s something to celebrate.