In yesterday’s post, we described why homeownership is such a risky financial proposition for low income households, who tend to be disproportionately people of color. From a wealth-building standpoint, lower income households tend to buy homes at the wrong time, in the wrong place, face higher financing costs, and have less financial resilience to withstand the fluctuations of housing and economic markets. Yet we continue to persist the the belief that homeownership is a universal elixir for wealth building. In fact, there’s some strong evidence that our excessive investment in housing–and our subsidies for homeownership have worsened our income inequality problems. This suggests it might be time to rethink our national outlook on housing and wealth building.

Has Homeownership Actually Heightened Inequality?

New research from Zillow’s Svenja Gudell shows that the collapse of the housing bubble actually worsened inequality. Modestly priced homes saw the biggest price declines, and the households who owned these homes lacked the equity to cope with the downturn, and were much more likely to be foreclosed upon: “When the bubble popped, less-expensive homes—often bought by low-income homeowners—were more likely to be foreclosed on than higher-end homes.”

In many important respects, the case for home-ownership as wealth creation is a circular argument: We proclaim that housing is a great investment, and encourage families to go heavily into debt to purchase homes, and then use the fact that so much household wealth is tied up in housing to justify additional subsidies and regulations to drive up home values. These regulations include local zoning (which limits the supply of housing, helping drive up prices or as it’s usually expressed “to protect property values”), but go much further. The federal government directly or indirectly provides or guarantees most home mortgages (and prices lower and terms more favorable that would be the case in a purely private market). And the federal tax code provides something on the order of a quarter of a trillion dollars in annual subsidies to homeownership. If homeownership is a good investment, it’s substantially because government policies have made sure that it pays off.

From a distributional standpoint, it’s clear that the emphasis on homeownership has actually led to a greater concentration of wealth, and not greater equality. As Matthew Rognlie showed virtually all of the increase in wealth inequality in the United States in the past four decades is accounted for by the increase in the share of capital in housing. Mian and Sufi plotted the ratio of the amount of home equity owned by the highest income quintile compared to the middle quintile of the US population. In the 1990s, a household in the highest income quintile had about 5 times as much housing equity as the average, middle quintile. By 2010, this difference had nearly doubled: to 9 times as much housing equity.

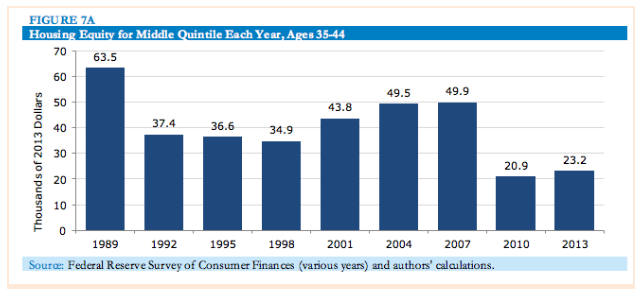

Particularly over the past decade, housing has a poor record as a wealth creator. Overall, homeowners collectively lost something on the order of $7 trillion in the collapse of the housing bubble. To put that number in some perspective, consider the average home equity of a household in the middle of the income distribution, with a household head aged 35 to 44 years. Data compiled from the Fed’s Survey of Consumer Finance by David Rosnick and Dean Baker shot that while inflation-adjusted home equity for this group grew from 1992 through 2007, since then it has fallen sharply; today the households in the middle quintile of this age group have less than half as much home equity as in 2007.

Time to Rethink Homeownership?

The collapse of the housing bubble erased all of the growth in the homeonwership rate in the United States since 1980. On the upswing, the bubble generated lots of (paper) wealth, and drew millions of households into ownership. The homeownership rate peaked at more than 69 percent in 2007, then plunged to less than 64 percent, as millions of households lost their homes.

The aftermath of the bubble should remind us that homeownership is a risky endeavor, and that for a substantial portion of the population, it’s not a feasible or prudent strategy for trying to build wealth. It’s time to re-think the role of homeownership in promoting wealth, especially for the poor. There are three big takeaways here:

- Pushing homeownership as a universal wealth building strategy for the poor, is a snare and a delusion. Its likely to hurt many families. Policies that lower the bar for home purchases, like very low down payment loans, may actually expose those least able to handle the risks of homeownership to even greater probability of loss.

- The efforts to extend homeownership down the economic spectrum in many ways simply constitute a way of providing political cover for subsidies like the mortgage interest deduction that chiefly benefit upper income households, thus actually worsening income inequality.

- As a nation, we have no substantial policy for helping renters build wealth. More than a third of our population, including its youngest, poorest, and people of color are, will continue to be renters. We might, for example, consider repurposing some of the $250 billion annually in federal tax subsidies to homeownership to help reduce rental costs or subsidize savings programs for renters.