There’s a huge demographic divide between those who use freeways and neighbors who bear their costs

When it comes time to evaluate the equity of freeway widening investments, it’s important to understand that there are big differences between those who travel on freeways and those who bear the social and costs in the neighborhoods the freeways traverse. Our equity analysis of the proposed half-billion dollar I-5 Rose Quarter freeway widening project shows:

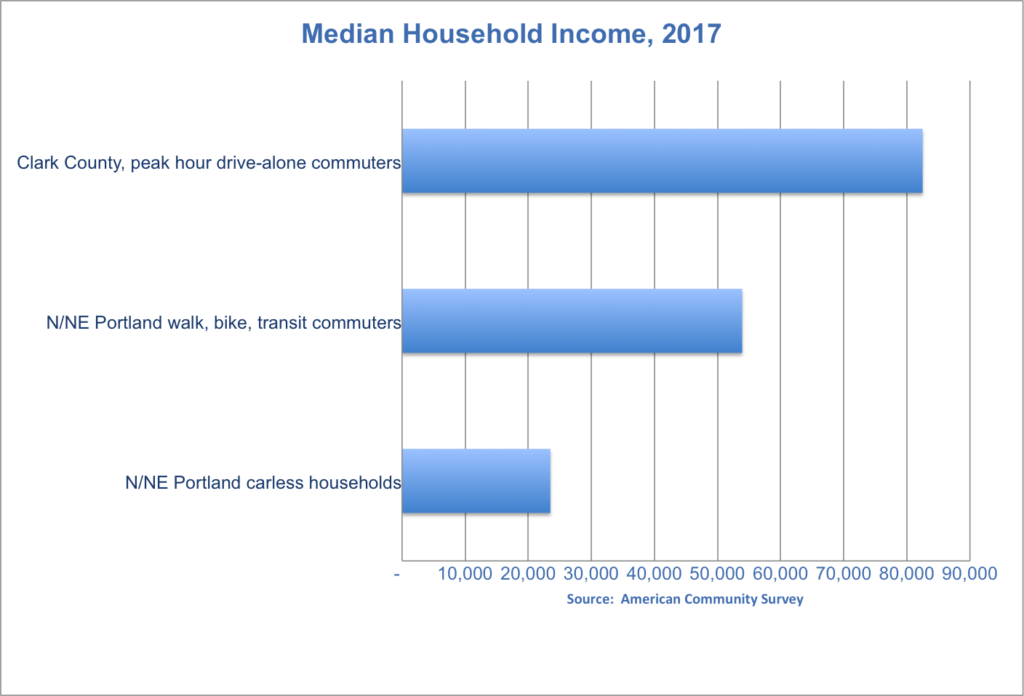

- Peak hour, drive-alone commuters from Clark County to Oregon have a median household income of $82,500, 50 percent greater than the transit, bike and walk commuters living in North and Northeast Portland ($53,900), and more than three times greater than carless households in North and Northeast Portland (23,500).

- Two in five (40 percent) of peak hour drive alone commuters from Clark County to Oregon have a median household income of more than $100,000.

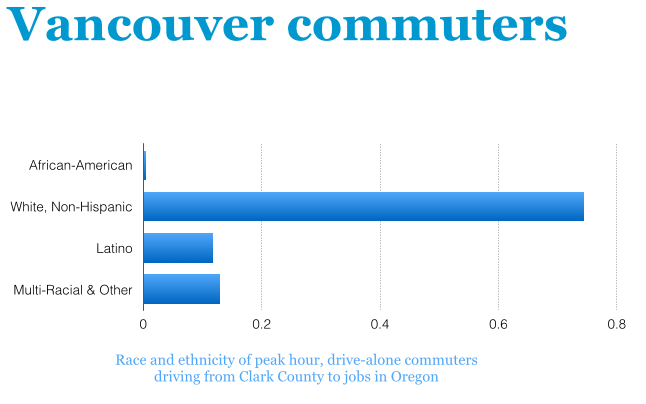

- Three-quarters of peak hour, drive-alone commuters from Clark County to Oregon are white, Non-Hispanic. Two-thirds of Tubman Middle School Students are persons of color (including multi-racial).

- Nearly half of all Tubman Middle School Students qualify for free and reduced price meals.

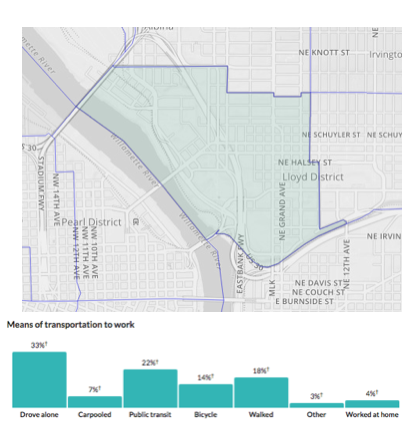

- A majority of those who live in the project area (Census Tract 23.03), commute to work by transit, bike or walking.

How should we judge the equity or fairness of our transportation system, and of proposed investments? One way is to look at the demographic characteristics of those who receive the benefits and who bear the costs of these investments. Today, we take a close look at the allocation of the costs and benefits of the proposed $500 million Rose Quarter Freeway widening project in Portland. The project would widen the freeway from four lanes to six, and rebuild associated interchanges to create straighter, faster routes for vehicles entering and leaving the freeway. The project also claims benefits for bikes and pedestrians, but that’s actually very questionable, as the project eliminates entirely one low-speed, pedestrian and bike friendly street that crosses the freeway (Flint Avenue), and creates a pedestrian and bike hostile miniature diverging diamond interchange (where multiple lanes of traffic will be traveling on the wrong (left) side of the road, to speed cars on and off the freeway). The wider freeway will add more traffic and more emissions to the neighborhood.

For this analysis we compare and contrast the demographics of two different groups: peak hour freeway users and neighborhood residents. Peak hour freeway users will be the primary beneficiaries of the Rose Quarter Freeway widening project. On a regular basis, this portion of Interstate 5 is congested in a very particular pattern: daily flows of commuters from Washington state (southbound in the morning, and northbound in the afternoon) are primarily responsible for congestion in this area. The impacts of this project, in terms of local traffic and air pollution, are primarily felt by those who live, work and go to school in the project area. Our analysis looks in more detail at two groups: drive-alone peak hour car commuters from Clark County Washington who work in Oregon, and persons who live or attend school in the project area. We look at three different sub-groups of persons living in the project area: residents of the Census Tract in which the project is located (Census Tract 23.03), persons living in North and Northeast Portland, and students attending the Tubman Middle School (which is located immediately adjacent to the Interstate 5 freeway). We look at two principal socioeconomic dimensions of these groups: household income and race/ethnicity.

Household Income

There’s a huge income disparity between those who commute by car on freeways from Washington to jobs in Oregon, and those live in the project neighborhood who walk, bike and take transit to their jobs. Peak-hour solo car commuters from Clark County Washington have incomes more than 50 percent higher than those who live in the neighborhood affected by the freeway widening who take walk, ride bikes or take buses to their jobs.

How do the incomes of those who will benefit from the freeway widening project (peak hour drive alone commuters, many from Washington State) compare to the incomes of those who will be affected locally by the increased traffic and emissions? There will undoubtedly be winners and losers from the Rose Quarter freeway widening project. While the project allegedly saves travel time for those who commute on the freeway, there are few if any benefits for those who ride transit, bike or walk in the project area. By many standards, the Rose Quarter project will make things worse. Bike riders will face more circuitous and steeper routes. Pedestrians will have to deal with “wrong-way” traffic on the project’s miniature diverging diamond interchange, and also cope with wider turn radius intersections–and faster moving cars–at the project’s “improved” freeway on-ramps.

We used Census data to look at the average household income of persons commuting during peak hours by themselves by automobile from homes in Clark County Washington to jobs in Oregon. Using data from the American Community Survey’s Public Use Microsample, we looked for solo car commuters who left their homes in Clark County between 6:30am and 8:30 am on a typical day. On average, the median peak hour solo car commuter had a household income of $82,500.

For contrast, we computed the average incomes of persons who live in North and Northeast Portland, and who commute to work by walking, riding bicycles or by transit (including bus, streetcar and light rail). The median walk/bike/transit commuter living in these neighborhoods had an average household income of just $52,900. We can also look at the average income of non-car-owning households in North and Northeast Portland. By definition, these households are largely dependent on transit, walking and cycling to meet their travel needs. The average income of non-car-owning households in this area is $23,000

Race and Ethnicity

There are profound differences in the race and ethnicity of those who will be the primary beneficiaries of this project (peak hour, drive alone commuters, chiefly from Washington State), and those who will bear the environmental consequences of the project (exemplified by Tubman Middle School students) who will breathe the emissions and cope with the increased car traffic associated with the project. This is apparent when we examine the racial and ethnic composition of these two groups. Peak-hour drive alone commuters from Washington State to jobs in Oregon are overwhelmingly White and non-hispanic; students at Tubman are overwhelmingly persons of color.

A majority of students attending Harriet Tubman Middle School are students of color according to demographic data collected by Portland Public Schools. About two-fifths of students are African American, about one-in-seven are Latino, and just one in three are white, non=Hispanic.

Clark County auto commuters to Oregon are overwhelming white, non-Hispanic. The American Community Survey provided data on the race and ethnicity of peak-hour drive alone commuters who travel from Clark County to jobs in Oregon. Three quarters of all drive-alone peak hour car commuters from Vancouver are white, non-hispanic.

In addition to being primarily persons of color, students at Tubman come from households with high levels of economic distress. Roughly half of all students (48.9 percent) attending Harriet Tubman Middle School qualify for free- or reduced-price meals, and indicator of low socio-economic status, according to data compiled by Portland Public Schools.

Widening a freeway through a neighborhood that doesn’t drive

In addition, data from the Census allows us to look in more detail at the usual mode of transport to work by persons living in the immediate vicinity of the project. This area is Census tract 23.03, and area that almost completely includes the entire portion of the freeway to be widened, as well as housing and commercial areas on either side of the freeway. According to the latest Census data, a majority of the persons living in this area commuted by transit, biking or walking. Only a third of local residents commuted alone by automobile. This makes this neighborhood one of the most car-free in the city. Census tract 23.03 has the highest proportion of bike, walk and transit commuters of any neighborhood outside downtown Portland. Fully 97 percent of Multnomah County residents live in neighborhoods that have lower levels of transit use, cycling and walking than this Census tract.

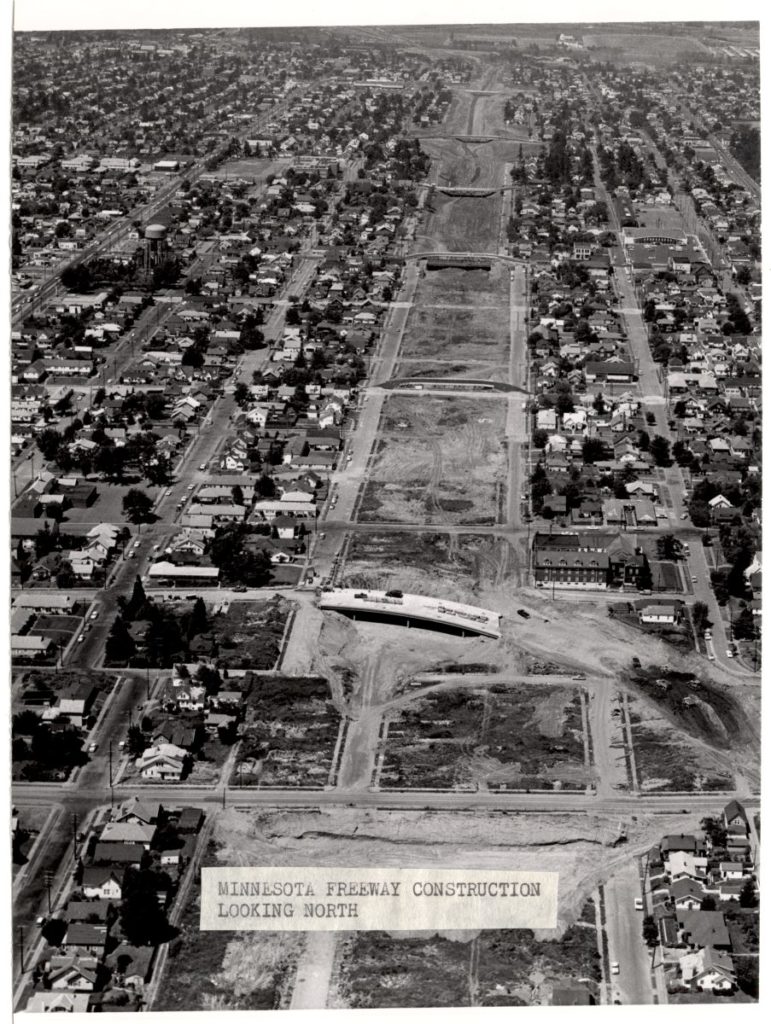

One of the so-called rationales for the freeway project is to somehow repair the damage to the neighborhood caused by construction of the freeway in the early 1960s. It’s difficult to understand how widening the damaging freeway redresses these damages. As we’ve documented at City Observatory, the construction of the freeway led to the Oregon Department of Transportation to demolish of more than 300 homes, which it never replaced. What the freeway expansion clearly does, however, is repeat the historical injustice done by freeway construction in the first place: subsidizing travel for higher income persons who live outside the neighborhood, while doing essentially nothing to better meet the needs of lower income persons who live in and neary the project’s location.

Technical notes: For North and Northeast Portland, we used data from Public Use Microsample Areas (PUMAs) 01301 and 01305, which include all of North Portland, most of Northeast Portland, and some portions of Southeast Portland. PUMAs are the smallest geography for which income by mode data are available for Portland. Data are for the 2017 ACS one-year sample. These data are from Ruggles, et al.

Steven Ruggles, Sarah Flood, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, Erin Meyer, Jose Pacas, and Matthew Sobek. IPUMS USA: Version 8.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2018. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V8.0