Metro’s multi-billion dollar transportation package does nothing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions

Spending $3 billion reduces Portland’s transportation greenhouse gases by .05 percent

This package costs nearly $40,000 per ton in reduced GHG emissions

Metro Portland knows that climate change is one of the most serious problems we face. We know that transportation, particularly automobiles are the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions. Our state, region and city have all formally adopted legal commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Officials from throughout the region say that dealing with climate change is one of the key priorities of a proposed multi-billion dollar transportation package. But in reality, this package will do virtually nothing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

A bit of background: Portland’s regional government, Metro, has convened a year-long process to develop a multi-billion dollar transportation spending proposal. The process is down to selecting projects to receive funding. According to Metro, one of the project’s core values is to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Early on in this process, the Metro Council set the direction for this package, saying:

Our imperative to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and prepare for a climate-change future is increasing.

More broadly, Metro’s Transportation Work Plan sets six specific outcomes for its Regional Transportation Plan, including:

Climate leadership – The region is a leader in minimizing contributions to global warming.

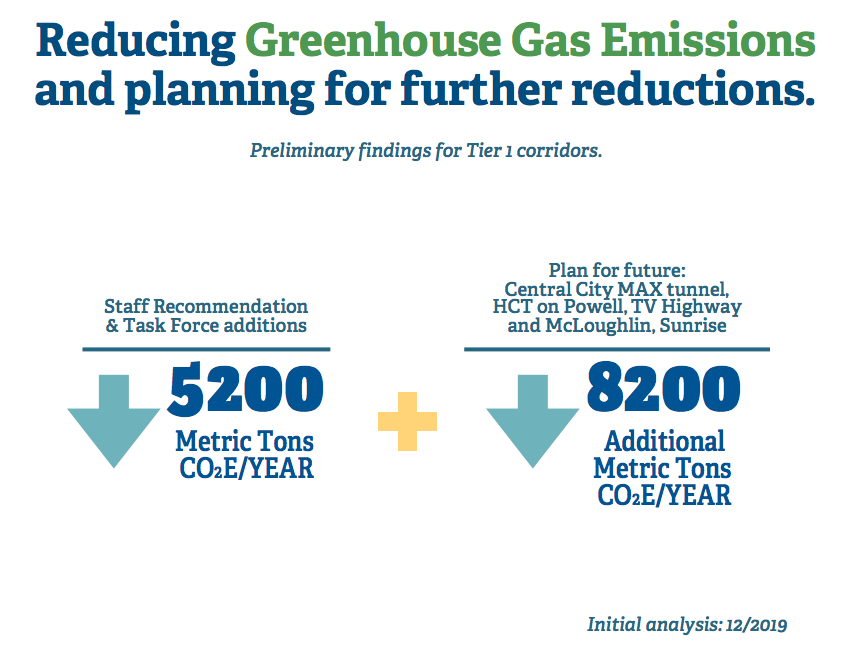

It sounds pretty bold, but until recently, there’s been little indication how the proposed multi-billion project list will advance the climate agenda. On December 18, for the first time, Metro staff presented their estimates of the decrease in greenhouse gas emissions associated with the approximately $3 billion proposed spending package. They estimate that the combined effect of the investments would be to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by about 5,200 tons per year.

Task Force members were quick to ask for a bit of context (not everyone has immediate access to an inventory of the region’s greenhouse gas emissions). Metro staff were at a loss at the time to come up with any figure for a total regional greenhouse gas emissions.

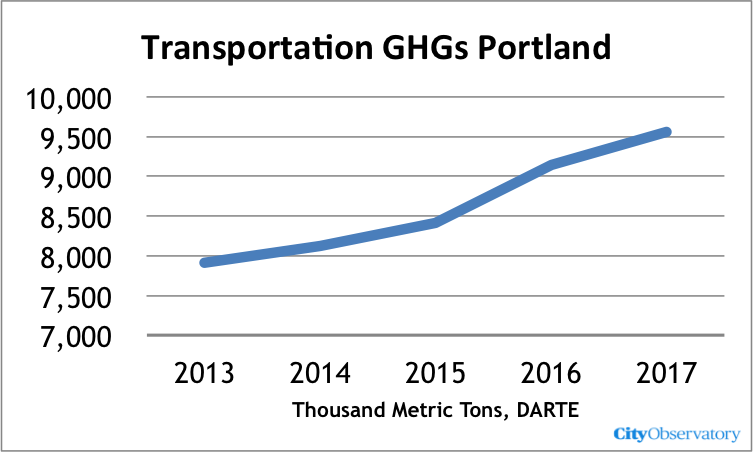

Let us help: Data from the national DARTE transportation emissions database show that in 2017 (the latest year for which data are available) the Portland metropolitan area had transportation greenhouse gas emissions of 3,892 kilograms per capita. The region’s population was 2,456,000. That puts total greenhouse gas emissions from transportation in the Portland area at about 9.5 million metric tons (2,456,000 x 3,892 /1000).

And its not like this number should be so difficult for Metro staff to determine. Their own “Climate Smart” Strategy, published five-years ago estimated that greenhouse gas emissions from “light-duty” vehicles (cars, SUVs and light trucks) were about 5.2 million tons in 2010. (That estimate omits emissions from larger trucks, buses, and other modes of transportation, and also is apparently just for the area inside metro’s urban planning boundary–but its clearly in the same ballpark as the DARTE estimates).

So here’s what Metro’s $3 billion transportation plan buys in terms of carbon emission reductions. That 5,200 tons per year of reduced greenhouse gas emissions works out to five one-hundredths of one percent of all the greenhouse gases currently emitted from transportation: 0.05 percent.

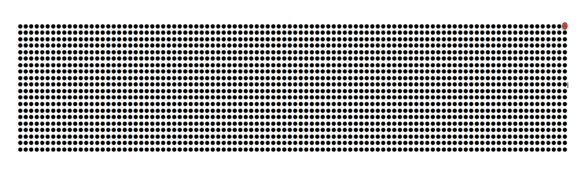

That may be a little bit difficult to visualize, so we’ve prepared a diagram that shows just how big this reduction is. The following graphic shows 2,000 dots, each corresponding to a little less than 5,000 tons of annual greenhouse gas emissions. The greenhouse gas reductions attributable to Metro’s 2020 transportation package are equal to one slightly over-sized red dot in the upper right hand corner of the chart.

That’s a trivially small reduction; its about the amount of greenhouse gases produced by fewer than 6 hours of driving in the Portland metropolitan area. It is so tiny that its within the margin of error of estimates of overall greenhouse gas production. Also, keep in mind that transportation, while the largest single source of greenhouse gas emissions in the Portland area is about 40% of the total. That means that the reduction in greenhouse gases based on the total is about 0.025%.

There’s a second way to put this number in context. Transportation-related greenhouse gas emissions in Portland have been increasing for the past four years according to the DARTE database. In fact, emissions are up substantially, by about 1,000 pounds per person annually over the level of 2013. In 2013, total transportation greenhouse gas emissions were approximately 7.9 million tons in the Portland area. That rose steadily to 9.5 million tons in 2017, mostly due to the big per capita increase in emissions, that in turn are attributable to the 40 percent decline in gasoline prices in 2014. So, on an annual basis, Portland area transportation emissions were about 1.6 million tons higher in 2017 than in 2013. The annual rate of carbon emissions increased by about 4,500 tons per day over the past four years. That means that the 5,200 ton yearly reduction in carbon emissions works out to the equivalent of offsetting less than a day and a half of the growth in annual carbon emissions we’ve recorded over the past several years.

So on this chart, if Metro’s 2020 projects were in place today, we would expect regional greenhouse gas emissions to decline by about 5,000 tons, from roughly 9,560,000 tons today to about 9,555,000 tons with the Metro projects. On this chart, that difference is simply invisible: For reference, the blue line on the chart is about 100 tons wide, or about 20 times larger that the reduction in greenhouse gases associated with the Metro plan. Despite the high-minded rhetoric, Portland’s proposed multi-billion dollar transportation initiative does effectively nothing to reduce the region’s transportation-related greenhouse gas emissions. Finally, it has to be said that we are taking Metro staff’s estimates of the greenhouse gas reductions associated with the spending package at face value. The agency hasn’t disclosed how these estimates were generated, and seems unlikely that Metro’s travel modeling has accounted for the induced demand for travel that would come might be caused by capacity increases and traffic flow improvements in the spending package. Alarmingly, Metro has propagated the fiction that the region’s greenhouse gases can be reduced by speeding traffic to reduce time spent idling, a claim that we’ve repeatedly debunked. A careful independent analysis of the environmental effects of this spending program might show it increased greenhouse gas emissions, rather than decreasing them.

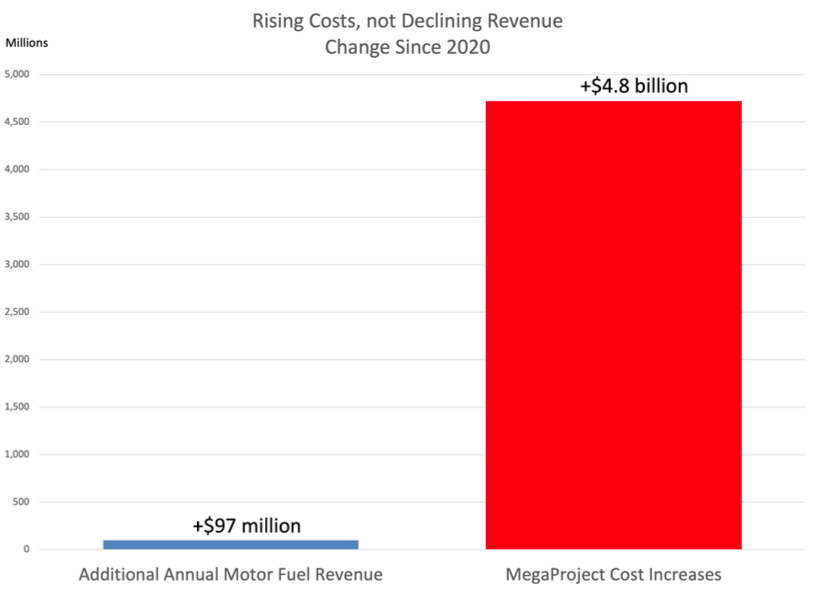

The price of carbon savings

It’s worth considering how much those carbon reductions cost. The total cost of this package is about $3 billion; that amount has an annualized value of roughly $200 million at a 5 percent interest rate. The annualized cost of the Metro transportation plan (about $200 million per year) divided by annual reduction in the number of tons of greenhouse gases is $200,000,000 / 5,200 = $38,500 per ton.

Of course that’s a crude estimate for a variety of reasons. Reducing greenhouse gases isn’t the only objective of the transportation package, so arguably some of the cost is aimed at achieving other objectives. But its also the case that the investment package doesn’t cover the entire costs of many of the projects. For example, the package’s largest project is a proposed Southwest Light Rail extension, of which the package would cover only about one-third of the capital cost.

Does it make any sense to spend nearly $40,000 to reduce a ton of carbon? There’s a lot of debate about the “social cost of carbon” with current estimates running roughly $50 per ton, and some economists speculating that the threat of climate change may necessitate of charge of several hundred dollars per ton to fully reflect climate costs and encourage the needed level of emission reductions

Just as a hypothetical, let’s ask how much it would take to achieve a 50 percent reduction in transportation related greenhouse gas emissions from current levels making this kind of investment. Current transportation emissions are slightly more than 9.5 million tons per year. To reduce that to 4.75 million tons per year at a cost of $40,000 per ton would cost on the order of $190 billion per year. To put that number in context, that is more than three times the total personal income of the Portland metropolitan area — about $57 billion per year.