As recently as the years 2002 to 2007, outlying urban neighborhoods and suburbs experienced much faster job growth than urban cores. But as a February 2015 City Observatory report, “Surging City Center Job Growth,” documented, that pattern reversed from 2007 to 2011, with urban cores overtaking more peripheral areas and maintaining positive job growth through those recession years. Since that report, however, the Census’ Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics database has released three more years’ worth of jobs figures, allowing up to update these trends for 2012, 2013, and 2014.

Using the same methodology as the 2015 report on the 51 largest metropolitan areas, we find that the relatively increased strength of city centers (which we define as areas within three miles of the central business district, or CBD) has held well into the post-recession recovery. While cores are now growing more slowly than the peripheries, the gap has narrowed substantially compared with the last economic cycle—a notable shift after decades of consistent job sprawl.

From 2002 to 2007, average annual job growth in urban cores was 0.26 percent, and 1.09 percent in peripheral, non-core areas. (These numbers differ slightly from those in the original report because of revisions from LEHD itself, as well as a data quality screen we implemented, which is explained at the bottom of this post. After applying the data screen, we based our findings on 19 of the 51 largest metropolitan areas. Numbers from all 51 MSAs are included at the end of this post.) From 2007 to 2011, this pattern reversed, with average annual job growth of 0.49 percent in urban cores and just 0.10 percent in peripheries. And from 2011 to 2014, while annual employment growth in non-core areas rebounded from the depths of the recession to 2.04 percent, it also improved in city centers, growing to 1.97 percent.

In other words, while city centers lagged metropolitan peripheries in average annual job growth by 0.83 percentage points from 2002 to 2007, from 2007 to 2014, urban cores have actually grown 0.19 percentage points faster than peripheries. And although peripheries have grown slightly faster since 2011, urban cores remain in a much stronger position than they found themselves in during the previous economic expansion. The persistence of this pattern suggests that the dramatic decline in job sprawl we found from 2007 to 2011 was not simply a temporary result of the recession, but is enduring through the current economic recovery.

One of the biggest challenges in the perennial discussions of city versus suburb job growth is how to define the core and the periphery, and where to get accurate date. In this post we describe why we think the three mile radius measure is a better indicator of the health of metropolitan cores, particularly for comparisons. We also discuss the strengths and limitations of data available to measure core employment. Despite the improvements in the geographical detail of data sets, there are still important limits.

These findings have major implications for American cities. We believe the evidence suggests the decline of job sprawl is a positive development, for at least three reasons.

First, many of the nation’s leading economists now agree that dense, walkable employment centers lead to improved productivity and economic growth. When firms cluster geographically such that the cost of travel between them is reduced, they are able to share resources such as physical infrastructure, labor pools, information, and technological or organizational innovation. According to research by Harvard professor Ed Glaeser, per capita productivity increases by four percent as population density increases by 50 percent—a difference roughly equivalent to the gap between Dallas (at about 3,600 people per square mile) and San Jose (at about 5,600).

Second, when people and jobs relocate to urban centers, they reduce carbon emissions in at least two ways. The first is by replacing some car trips with more emissions-efficient modes, like public transit or carpooling, or with zero-emissions modes, like walking or biking. As we have noted at City Observatory, jobs in central cities, which tend to be public transit hubs, make it more likely that even workers who live in outlying suburbs will use transit. In addition, even when commuters continue to drive, they are likely to drive fewer miles when jobs are located in central areas, reducing their emissions.

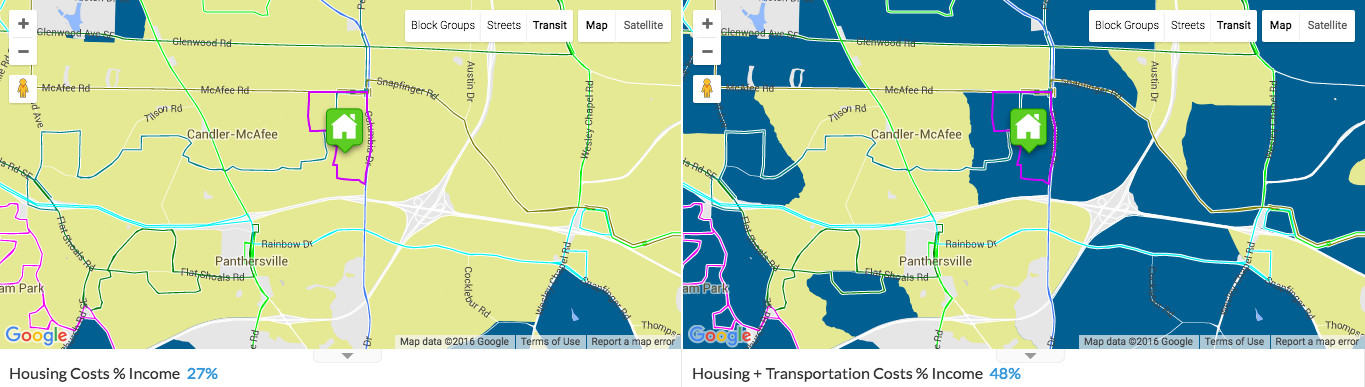

Finally, by allowing commuters to use less costly forms of transportation—public transit, walking, or biking—the movement of jobs to central cities can be a significant boon to social equity. Low-income workers are particularly sensitive to the high costs of car ownership and use, and researchers such as those at the Center for Neighborhood Technology have shown substantial differences in average transportation costs between denser, closer-in neighborhoods and more outlying communities. In many cases, the option of not using a car is worth several thousand dollars a year, a crucial increase in disposable income for many households.

But policymakers cannot trust that this trend will simply continue on its own, or that it will not pose challenges that will need to be addressed. In many places, the growth of demand for living and working in city centers has outstripped the growth of actual room for people to live and work in urban environments. This may be a result of some combination of a slowness of market actors to respond to demand; physical constraints on the growth of living and working space; or regulatory constraints on that growth.

This dynamic has produced a shortage of cities—demand for real estate in these central cities exceeds supply, driving up prices, excluding those who cannot afford them, and slowing the growth of these in-demand urban cores. Addressing this shortage, and making sure that residents outside the core have high-quality access to employment there with sustainable, low-cost transportation like public transit, biking, and walking, is key to leveraging this trend for maximum benefit in American cities.

How to measure the “core”?

While this report uses a three-mile radius around a city’s central business district as a proxy for “city center,” there are other ways to aggregate employment data at the sub-metropolitan level. One such method is to use counties, for which data is updated more regularly than the LEHD database our method relies on.

A recent example of this type of county analysis was published by former Trulia chief economist Jed Kolko in January 2016. Kolko’s data shows that while counties at the center of large metropolitan areas have seen job growth since 2007, they are outpaced by suburban counties in the same regions—although central counties have improved the most compared to patterns observed in 2000-2007, and appear to be continuing that acceleration. He further argues that to the extent that employment growth in these urban counties does appear to be gaining steam, it’s too early to tell whether that trend is cyclical or more long-term.

This analysis provides another useful perspective, but as we’ve pointed out, it also has limitations. In many instances, county-level data are too geographically coarse to detect shifts in growth patterns within metropolitan areas. Central counties seldom correspond to the central city of a metropolitan area, and even more rarely to what locals would understand as the “urban core.” In many cases, central counties include substantial suburban job centers: Microsoft’s suburban campus in Redmond, Washington, is in Seattle’s King County, for example, and the suburban office parks around O’Hare Airport are part of Chicago’s Cook County. Moreover, county sizes vary substantially from region to region.

Even so, Kolko’s county-level data shows that—consistent with the data reported here—central areas’ job growth performance has improved in 2007-15, compared to the economic expansion of 2001-07. It also shows that job growth is accelerating faster in urban counties than in suburban counties in large metropolitan areas.

A key question raised by Kolko is whether the relative improvement in job growth in urban cores is a temporary cyclical change—one which will disappear as the economy normalizes—or a long-term structural shift in the relative fortunes of central and peripheral locations. While we may not have a definitive answer for several years, both the data presented here and Kolko’s county-level data suggest the answer is the latter. Far from being a temporary artifact of the recession, the improvement of urban cores is continuing into the current economic expansion.

Methodology and data notes

The data for this report are drawn from the Census Bureau’s Local Employment and Housing Dynamics program which combines administrative data to estimate employment levels by street address for workers and employers. Compiling these data is a complicated process and hinges on the consistency with which administrative records are compiled. In the course of looking at employment data for 2012-2014 from LEHD, we discovered a number of instances of year-to-year job changes in both core and non-core areas that were so large as to raise questions about the reliability of the data. In some cases, there were periods of one to two years in which data for a particular geography exhibited a major departure from its historical pattern and then subsequently reverted to values close to the previous baseline.

For example, Detroit’s core is reported to have 140,507 jobs in 2002, but only 115,318 in 2003, and then 130,076 in 2004. Salt Lake City’s core displayed an even more curious pattern. In 2008, it reported 123,859 jobs; that fell to 110,649 in 2009. While a ten percent drop seems extreme, it did coincide with the Great Recession—but subsequent years are harder to explain. In 2010, reported employment increased again to 120,521; then fell to 104,823 in 2011; then grew again to 114,323 in 2012. These examples are not atypical for the metropolitan areas that failed our data quality screen.

These metropolitan areas are also typical of those with data anomalies in another way. Because LEHD breaks down employment by sector, we can determine that nearly all of the net job changes in the cores of Detroit and Salt Lake City occurred in “Educational Services.” (In Detroit, for example, LEHD reports the number of such jobs as 27,784 in 2002; 7,212 in 2003; and 27,797 in 2004.) Both of these cities have large universities within their cores.

These problems may be inherent in utilizing disparate sets of administrative records to establish workplace and residence locations. LEHD data are based on personal and business tax records which were not primarily designed for the purposes to which they are currently being adapted. In particular, it seems possible that year-to-year changes in these records at large organizations with multiple office sites switch between associating subsets of employees between the central office and some sort of satellite office. In most cases, large changes in one category—educational workers in the core, for example—are offset by changes in the other direction in another category—educational workers in the periphery. This hypothesis is also supported by the tendency for these changes to fall in the educational sector, or other categories—such as “Health Care and Social Assistance” and “Administration and Support”—likely to be part of large organizations. Our hypothesis, then, is that these administrative record changes, which do not necessarily reflect any actual physical rearrangement in the real world, are behind the odd data patterns we see.

Administrative data like that used to construct the LEHD database are not primarily intended to serve as a resource for time-series analysis. The Census Bureau constructs its estimates of data each year separately, so changes in reporting locations or disaggregations from year to year can alter results. As the Census Bureau warns: “The LEHD program produces each year of LODES independently, so there may be time series inconsistencies due to updates and methodological changes that can complicate longitudinal inferences.”

Validating all of the LEHD data is far beyond our resources. Instead, we chose to create a data quality screen focusing only on employment totals at levels of geography that might meaningfully affect our final analysis. The screen flagged metropolitan areas with large one-year changes in total employment: greater than eight percent in either direction in core areas, and greater than five percent in either direction in non-core areas. (The cutoffs differ because of the larger variance in growth figures for cores.) Metropolitan areas with such changes were excluded, unless the changes a) were consistent with multi-year trends, or b) were large declines during the Great Recession. As in our earlier report, we excluded the category of public administration from all totals. Federal employment was added to the LEHD program only after 2010, making later year data in this category non-comparable with earlier year data.

The Census’ LEHD program represents an invaluable source of data for social science research on any number of subjects: economic development, commute patterns, social networks, and many others. It has already been widely used for urban policy research, including by Elizabeth Kneebone and Natalie Holmes at the Brookings Institution (Kneebone & Holmes, 2015); researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland (Hartley et al., 2015), and others (Meltzer & Ghorbani, 2015). We are enormously grateful to the program for doing the work of compiling this information. However, we do want to flag these issues as a potential area of improvement, and suggest that other researchers using LEHD data should keep them in mind while performing their analysis.

| Included | Excluded—failed data quality screen | Excluded—incomplete data |

| Atlanta, GA | Austin, TX | Boston, MA |

| Baltimore, MD | Buffalo, NY | Phoenix, AZ |

| Birmingham, AL | Charlotte, NC | Washington, DC |

| Cincinnati, OH | Chicago, IL | |

| Cleveland, OH | Columbus, OH | |

| Denver, CO | Dallas, TX | |

| Hartford, CT | Detroit, MI | |

| Houston, TX | Indianapolis, IN | |

| Kansas City, MO | Jacksonville, FL | |

| Las Vegas, NV | Los Angeles, CA | |

| Louisville, KY | Memphis, TN | |

| Nashville, TN | Miami, FL | |

| New York City, NY | Milwaukee, WI | |

| Pittsburgh, PA | Minneapolis, MN | |

| Portland, OR | New Orleans, LA | |

| Rochester, NY | Norfolk, VA | |

| San Antonio, TX | Oklahoma City, OK | |

| San Diego, CA | Orlando, FL | |

| San Francisco, CA | Philadelphia, PA | |

| Providence, RI | ||

| Raleigh, NC | ||

| Richmond, VA | ||

| Sacramento, CA | ||

| Salt Lake City, UT | ||

| San Jose, CA | ||

| Seattle, WA | ||

| St. Louis, MO | ||

| Tampa, FL |

To test whether our data screen biased the overall results, we also tabulated aggregate data with no exclusions. Although the totals differ somewhat, the trends are broadly similar: average annual employment growth in urban cores is 0.00 percent from 2002 to 2007, 0.42 percent from 2007 to 2011, 1.60 percent from 2011 to 2014, and 0.92 percent from 2007 to 2014. Average annual employment growth in non-core areas is 1.23 percent from 2002 to 2007, -0.10 percent from 2007 to 2011, 2.01 percent from 2011 to 2014, and 0.81 percent from 2007 to 2014.