Our recent conversation about the future of American driving habits, and the role of the price of gas in changing them, is a good reminder of a broader truth about transportation policy: prices are important, and getting prices right (or wrong) is crucial. And when it comes to driving, prices are frequently wrong.

That’s because driving is extremely costly: It uses vast amounts of valuable urban land and requires the construction and maintenance of public infrastructure. But it also has massive negative spillover effects, from forcing cities to sprawl more than they would otherwise (because of all that land used for parking and driving compared to more space-efficient transportation modes), to pollution and environmental damage, to the public health crisis of deaths and injuries caused by car crashes.

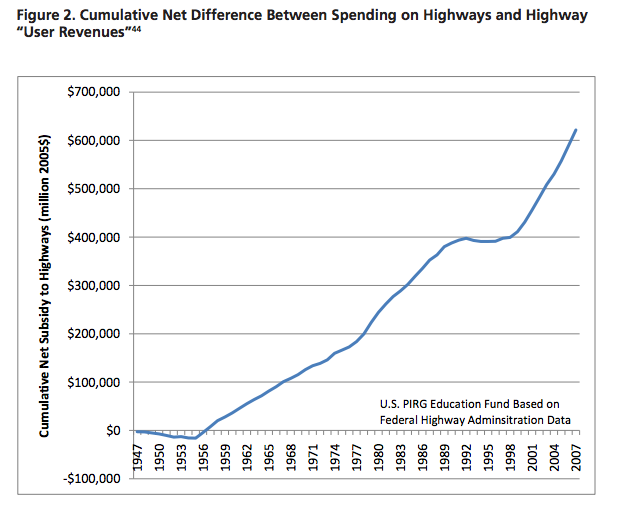

But drivers see very little of this in the price of using their vehicles. A study released earlier this year busted open the myth that drivers “pay their way”—even only counting the direct costs of maintaining their transportation infrastructure—through the gas tax. In fact, those revenues cover less than half the cost of building and maintaining road networks. Below, we’ve republished our writeup of that report (originally entitled “There’s no such thing as a free way”), which remains a hugely important piece of context for any debate over the future of transportation policy. A big takeaway: While gas prices are an important part of the cost of driving, they’re only a part. We ought to use other levers, from taxes to congestion and parking charges, to get the price of driving right.

A new report from Tony Dutzik, Gideon Weissman and Phineas Baxandall confirms, in tremendous detail, a very basic fact of transportation finance that’s widely disbelieved or ignored: drivers don’t come close to paying the costs of the roads they use. Published jointly by the Frontier Groups and U. S. PIRG Education Fund, Who Pays for Roads exposes the “user pays” myth.

The report documents that the amount that road users pay through gas taxes now accounts for less than half of what we spend to maintain and expand the road system. The shortfall is made up from other sources of tax revenue at the state and local level. This subsidization of car users costs the typical household about $1,100 per year – over and above what they pay in gas taxes, tolls and other user fees.

While recent congressional bailouts of the Highway Trust Fund have made the subsidy more apparent, it has actually never been the case that road users paid their own way. Not only that, but the amount of their subsidy has steadily increased in recent years. The share of the costs paid from road user fees has dropped from about 70 percent in the 1960s to less than half today, according to the study.

There are good reasons to believe that the methodology of Who Pays for Roads, if anything, considerably understates the subsidies to private vehicle operation. It doesn’t examine the hidden subsidies associated with the free public provision of on-street parking, or the costs imposed by nearly universal off-street parking requirements, that drive up the cost of commercial and residential development. It also ignores the indirect costs that come to auto and non-auto users alike from the increased travel times and travel distances that result from subsidized auto oriented sprawl. And it also doesn’t look at how the subsidies to new capacity in some places undermine the viability of older communities (a point explored by Chuck Marohn at length in in his Strong Towns initiative.)

These facts put the widely agreed proposition that increasing the gas tax is politically impossible in a new light: What it really signals is car users don’t value the road system highly enough to pay for the cost of operating and maintaining it. Road users will make use of roads, especially new ones, but only if their cost of construction is subsidized by others.

The conventional wisdom of road finance is that we have a shortfall of revenue: we “need” more money to pay for maintenance and repair and for new construction. But the huge subsidy to car use has another equally important implication: because user fees are set too low, and because, in essence, we are paying people to drive more, we have excess demand for the road system. If we priced the use of our roads to recover even the cost of maintenance, driving would be noticeably more expensive, and people would have much stronger incentives to drive less, and to use other forms of transportation, like transit and cycling. The fact that user fees are too low not only means that there isn’t enough revenue, but that there is too much demand. One value of user fees would be that they would discourage excessive use of the roads, lessen wear and tear, and in many cases obviate the need for costly new capacity.

And these subsidies to car travel have important spillovers that affect other aspects of the transportation system. There’s a good argument to be made that part of the reason that subsidies to transit are as large as they are is that motorists are being paid not to use the transit system in the form of artificially low prices for road use and (thank you Don Shoup) parking.

There’s another layer to this point about roads not paying for themselves: Most of these calculations are done on a highly aggregated basis, and look at the total revenue for the road system, and the total cost of maintaining the road system. What the study doesn’t explore is whether particular elements of the road system pay for themselves or not.

Think about air travel for a moment. Airlines don’t simply look at whether their total revenue from passengers (fares and all those annoying fees) covers the total cost of jets, crews, and fuel (although the stock market pays attention to this). Airlines look at each individual flight and each route, and examine whether the number of travelers and the amount of fares that will be paid cover the cost of providing that service—when not enough passengers use a route, they discontinue air service (as many small market cities know too well). While this calculus is routine and well-accepted in air travel and the private market, it’s unknown for public roads.

The Frontier Group/US PIRG study also significantly understates the economic cost of the transportation system. Their analysis looks only at how much we are actually spending to maintain and expand the current system. This is problematic for two reasons. First, there’s abundant evidence that we’re not spending enough to keep the system in repair, and there’s a growing hidden cost in higher future repair bills from the added deterioration of the system. These hidden costs are accumulating and not reflected in what users pay now. Second, we’re doing nothing to recognize the economic value of the existing road system: the replacement cost of the current road system –what it would take to rebuild the existing asset—is likely on the order of tens of trillions of dollars. Current road users get free use of that inherited, paid for (but depreciating) asset. Again, this is unlike other forms of transportation: just because United Airlines may have long since paid off the purchase price of the 737 you are riding in, doesn’t mean that they don’t charge you for the capital value of using that asset.

The real question for transportation public finance is whether new roads—additional capacity—pays for itself. Does the volume of traffic using a new bridge or additional lanes of freeway capacity pay for the road they use in their road taxes? New projects are so expensive–$100 million or more for a mile of urban freeway–that the road users who pay the equivalent of 2-3 cents per mile of travel in gas taxes (depending on the tax rate and vehicle fuel efficiency) never contribute enough money to recoup the costs of the new capacity.

The surprising evidence from road pricing demonstrations (tolled HOT lanes) is that the revenue gathered from tolling often fails to cover the costs of collecting the tolls and operating the toll collection system: they never come close to paying for the roadway. (To be sure, tolling improves the efficiency of use of the freeway—traffic flows more smoothly, capacity is increased—but the tolls don’t pay for constructing, or even maintaining the pavement).

But again, the highly visible toll collection mechanism, like the very visible gas tax, creates the illusion that user fees are paying the cost of the system.

As the Transit Center demonstrated in its recent report, Subsidizing Congestion, the $7.3 billion federal tax break for commuter parking costs encourages additional peak hour car commuting which has the effect of causing greater congestion. The systematic under-pricing of roads has the same effect, with the result that taxpayers subsidize car use through higher taxes, and also face greater congestion than they would if road users paid their way.

To be sure, these same questions can, and should be raised about transit, biking and walking projects. And for transit projects, close financial scrutiny is far more common than for roads. A key difference with these other forms of transportation is that they arguably have big net social benefits–lower congestion, less pollution greater safety, and they support important equity objectives by making transportation available to those who don’t own or can’t operate a motor vehicle. The problem with hidden subsidies is that often that they’re hidden: if we made them explicit, and considered our alternatives we would likely choose differently and more wisely.

The problem of pricing roads correctly is one that will grow in importance in the years ahead. It’s now widely understood that improvements in vehicle fuel efficiency and the advent of electric vehicles is eroding the already inadequate contribution of the gas tax to covering road costs. The business model of companies like Uber and Lyft likewise hinges on paying much less for the use of the road system than it costs to operate. The problem is likely to be even larger if autonomous self-driving vehicles ever become widespread—in larger cities it may be much more economical for them to simply cruise “free” public streets than to stop and have to pay for parking.

As we’ve pointed out before, the root of many of our transportation problems is that the price is wrong. Puncturing the widely held myth that cars pay their own way makes this report required reading for those thinking about transportation finance reform.