Political rationalizations and exceptionalism will always be used to justify giveaway policies

With the possible exception of Greg LeRoy (who tracks state and local incentives for Good Jobs Now) and Amazon’s site location department, there’s no one in the nation who knows more about business incentives and their effectiveness than the Upjohn Institute’s Tim Bartik. Tim has written a bevy of careful academic studies of the impact of a range of tax incentives, most of which are a bit technical for a general audience. Thankfully, he’s distilled the key learnings into a thorough and clearly written non-technical summary of what the research shows. This new book–Making sense of incentives: Taming Business Incentives to produce prosperity , available in print and also as a (free) downloadable PDF, is must reading for anyone involved in economic development.

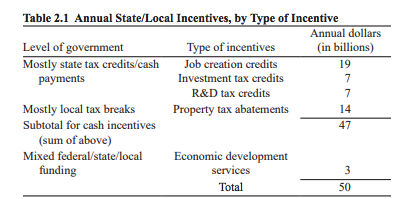

Economic incentives are big business. Bartik estimates that state and local governments hand out roughly $50 billion in incentives annually.

While there’s considerable folk wisdom about their efficacy, Bartik’s book takes a hard look at whether they actually work.

The “But For” problem

There are a couple of aphorisms that neatly summarize the problems and challenges of assessing economic development incentives.

“In know that only half of all advertising works, I just don’t know which half.”

“Shoot everything that flies, claim everything that falls.”

The gnarliest question in evaluating economic development incentives is figuring out whether they actually made any difference to where a firm ended up locating or not. Economic development deal-makers will swear up-and-down (and may even believe) that the last dollar of tax incentives that they provided “sealed the deal” and that without them the company would have gone elsewhere. Critics note that the abundance of incentives and the obsequiousness of economic development officials has produced as system of cash prizes for bad corporate behavior which rewards companies for doing exactly what they would have done anyhow, provided that they simply engage in the appropriate corporate kabuki of pretending to look seriously at multiple locations. Here’s where Bartik’s research shines: he’s used a range of economic techniques to assess whether and how much incentives actually matter to the location of business investment. His conclusion: roughly three-quarter of all incentives don’t matter; only about a quarter of the time do they tip the balance. Bartik explains:

For a new facility location or expansion decision, this means that the incentive tipped the location decision toward this state only 25 percent of the time or less. The other 75 percent of the time, the firm would have made the same new facility location decision, or same expansion decision, even if no incentive had been provided.

You’d think that would chasten economic development officials–and their bosses, Mayors and Governors. But it doesn’t. While Bartik is almost certainly right in the aggregate (three-quarters of incentives are wasted), its nearly impossible to tell whether any individual firm’s tax break was the “deal clincher” or simply a giveaway. Economic development officials seem to always believe (and nearly always say) that their incentive program was essential to the result. Corporate beneficiaries also have strong incentives to play along (to make their government partners feel justified in making the deal).

What this means in practice its rare that anyone ever questions whether a tax break or subsidy was actually the decisive factor in tipping a location decision. Economic development officials and the companies that get the tax break always say that it was a driver in their deal. Confronted with studies like Bartik’s the seasoned economic development practitioner may even concede that other people give away the store, but that our agency (or this deal) is one of those 25 percent where it made a difference.

Two bits of evidence from the field: Many economic development deals are composed of multiple incentives: state tax breaks, local tax breaks, subsidies for land development or job training, road or sewer or water line extensions and so on. It’s common for each of these programs to claim credit for all of the new jobs and investment associated with their particular incentive. Shoot everything that flies, claim everything that falls. Some decades ago, when I worked for the State of Oregon, I asked a state manager why her program had extended a subsidy to a firm after it had already announced its investment: the manager explained that it was a sure-fire win; her program would be able to claim credit for job creation, and that would make its benefits look even larger.

Politics trumps economics

Most of Bartik’s book is informed by careful econometric research that tests whether incentives seem to have any correlation with increases in business investment (they mostly don’t), whether they actually tip business decisions toward particular locations (about three-quarters of the time they’re irrelevant) and whether they generate more benefits that costs (again, usually not).

If Governors and Mayors were cool, fact-driven analysts, Bartik’s work (and that of other scholars) would be game, set and match. But as Bartik acknowledges, a primary motivation for offering incentives is political. Elected leaders want to be perceived as doing something to benefit the local economy, whether it works or not is something that’s only likely to be of interest and accessible to scholars like Bartik. When it comes to economic development, Governors and Mayors are involved in the production of “symbolic goods.” The more drama and publicity (as exemplified by the media coverage of Amazon’s carefully staged “HQ2” competition, the more opportunity for these elected leaders to show they “care” about voter’s economic concerns. Bartik understands this dynamic:

A political reason for incentives is that they are popular. Targeting the creation of particular identified jobs—which is what incentives do—is rewarded by voters. Voters are more likely to vote for politicians who offer incentives, even if the incentives are unsuccessful. Voters appreciate well-publicized efforts to attract jobs. If a governor or mayor can go after a prominent large corporation with an incentive offer, why not? At least he is trying; he cares. Better yet, the incentives may be long-term, paid for by the next governor or mayor. Political benefits now, budget costs later.

Some years back, I wrote an analysis of state and local efforts to attract and build biotechnology industry clusters. One thing that I observed was that, in addition to the chances of success being extremely remote for any city, it was certain that it would take a decade or more for any imaginable biotechnology development strategy to bear fruit. Since that would be well beyond the political lifetime of any incumbent Mayor or Governor, it seemed to me at first glance that biotech would be an unattractive strategy, because you would never be in office to get credit for success. Yet nearly every state and large city was actively pursuing biotech. Then it dawned on me: if success was at least a decade away, my city or state’s biotech efforts could never be judged a failure while I was in office. The critical takeaway: it is the political calculus that drives business incentives, not any consideration of whether they actually work in practice or not.

This observation is confirmed by the extraordinary paucity of practitioner-driven evaluation. Few economic development departments anywhere engage in systematic monitoring of the results of their efforts. They’re very good at creating an echo chamber for announcements of new investment, but seldom, if ever talk about whether job creation promises are met. Instead, the only solid, objective evidence on what works, and what doesn’t comes from scholars like Bartik, which is a key reason why this book is so important.

Concrete Advice

We’ll almost certainly continue to have business incentives. Most of them will continue to be ineffective. One of the most valuable pieces of Bartik’s book is four simple points about how to structure incentives to maximize their economic benefits and decrease their costs. They are:

- Focus incentives on traded sector industries (i.e. businesses that sell goods and services in national and international markets), rather than subsidizing local firms who compete largely against other local firms. Target these incentives for distressed areas.

- Emphasize services over incentives. Spending money on services that make businesses more competitive, like employee training, do more to produce benefits.

- Avoid big long-term deals, they’re generally bad deals for local governments, and “out-year” incentives actually have little effect on current business decisions.

- Pay for incentives by raising overall business taxes rather than cutting public services.

Bartik’s work is as close as definitive answers get to shedding light on the game of business incentives. He gives a coherent analysis of the “but for” problem, and demonstrates that most of what is spent on economic development has little impact on patterns of investment. Unfortunately the compelling political calculus for offering incentives continues to trump analytics.The book clearly delivers on the first half of its title (making sense of incentives). Accomplishing the second half, (taming them) will continue to be a difficult task, even with this good advice.

Timothy J. Bartik, Making sense of incentives: Taming business incentives to promote prosperity, Upjohn Institute, WE Series, October 2019 (https://research.upjohn.org/up_press/258/)