At City Observatory, we’ve cataloged a series of indicators that point to the the growing economic strength of city centers—including on the metric of job growth. But in a new blog post, Jed Kolko looks at county-level data for the past 15 years, and declares that city jobs aren’t really back, concluding: “It’s hard to make the case that economic activity has fundamentally become more urban.”

As for evidence that job growth in urban counties has picked up since 2007, Kolko calls that a “cyclical,” rather than “structural,” trend—i.e., one that is inherently temporary.

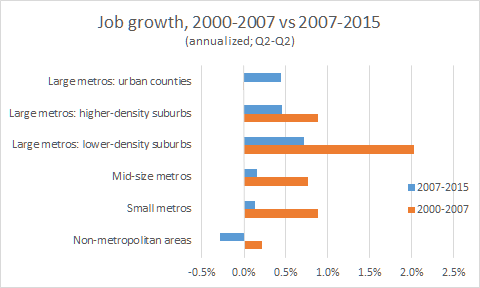

Kolko uses county level data on employment focusing on the period from 2000 to 2015, classifying counties in large metropolitan areas as either urban (if they are the most populous or central county in the metropolitan area), higher-density suburban (not the most central, but still densely settled), lower density suburban (in a metro area, but lower density). He also presents data on smaller metropolitan areas, and non-metro areas, but we’re going to focus on patterns within large metro areas.

We have a huge amount of respect for Jed Kolko and his work. But on this point, we respectfully but firmly disagree on the interpretation. We look at the same data, and draw some different conclusions—here’s why:

Central counties are accelerating; suburban counties have decelerated

Job growth in central, urban counties is accelerating. Central counties are growing faster in the 2007-15 cycle than in the 2000-2007 cycle. All other counties are growing slower than in the earlier period. So, for example, central county growth accelerated from zero in the 2000-2007 period to approximately 0.4 percent in the 2007-15 period; meanwhile growth in suburban counties decelerated—slowing from 0.8 percent in 2000-07 to 0.4 percent in 2007-15 in higher density suburbs, and slowing from 2.0 percent to 0.7 percent in lower density suburbs. Dense central counties are growing faster than they were before 2007; suburbs are growing more slowly than they were before 2007. That’s evidence that job growth is becoming “more urban.”

We’ve had two economic cycles since 2000, and central counties are doing better in this second cycle

Kolko downplays the significance of these changes by saying that they are simply cyclical, and describes the entire period 2000 to 2015 as a singular cycle. But since 2000 there have been two macroeconomic cycles, not one. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, there was a peak in 2000, a trough in 2001, another peak in 2007, and another trough in 2009 and we’re working towards another peak today. If we define a cycle as the time between two peaks, this 15-year period is very nearly two complete cycles. The key point is there have been two expansionary cycles in the last 15 years and the performance of central counties is very different in this most recent one. That suggests that this urban acceleration is actually its own phenomenon, and not simply a contractionary phase of a cycle whose growth favored the suburbs.

Even within the latest cycle, central counties are accelerating

Also, the within cycle pattern of change doesn’t square with this attempt to dismiss this as a cyclical change. Kolko’s argument is, implicitly, that the strength of cities was due to some temporary, special factors in the early post-2007 period. If that was the case, then one would expect the suburbs to reassert themselves as the cycle matured (and the the unchanged underlying structural advantages came into play). But Kolko’s evidence doesn’t square with that view: Central counties are performing better at the end of this cycle; if it were truly “cyclical,” then as the cycle progressed, you would expect suburbs to be erasing the difference. Instead, the pattern remains the same.

The other implication of the “no structural change” hypothesis is that Kolko expects growth trends to revert to the kind of housing bubble pattern of the 2000-2007 period. (Part of the reason suburban counties grew faster had to do with the growth of sprawling, single family subdivisions, and attending shopping centers and office parks.) There’s precious little evidence that those trends are re-asserting themselves.

The key point is that something very different is going on in the pattern of job growth within metropolitan areas in the period since 2007 than in the period prior to 2007. Kolko is essentially arguing that there’s no meaningful information to be extracted from subdividing that 15-year period into two segments—and that instead we need to look at the entire period as one trend. We disagree.

And finally, even if you regard 2000 to 2015 as a single cycle, there’s no reason to believe that the housing bubble was not the anomalous part. If you discount recent city growth using the cyclical argument, you’re suggesting that the 2000 to 2007 period was “normal,” and everything since then has been a temporary cyclical departure from that pattern. When this cycle is complete, and things return to “normal,” then we can expect the previous pattern to reassert itself. We don’t think so: the housing market continues to be weak, especially for the kind of sprawling, single-family development that propelled growth in the bubble.

County-based measures are crude and produce inaccurate comparisons

Finally, this is wonky, but it needs to be said: Counties are the wrong units for making these comparisons.Even “central” counties vary wildly from region to region in their size and centrality—and they often contain both urban and suburban areas. When they contain suburban areas, they’re often the kind of inner-ring suburbs that are seeing the worst economic performance. Central counties in some metros (Atlanta or Miami) are tiny (less than 10 percent of the MSA), while in other metros (San Jose, Phoenix, Jacksonville, or Austin), the central county makes up a majority or near-majority of the region’s economy. In some places, the central county includes a vibrant urban core and nearby neighborhoods, as well as declining older urban neighborhoods and industrial areas. A finer geographic parsing is needed to detect whether the urban core is growing.

For example, Chicago’s Loop and North Side could be gaining jobs like crazy (as they are) while suburban Cook County (especially the southern and western suburbs) could be losing jobs and population, and Kolko’s county level analysis would lump them together—missing or discounting the central job growth. Similarly, in the Seattle area, both Microsoft’s suburban Redmond campus and Amazon’s downtown South Lake Union headquarters are in the same county (King). Kolko’s county data simply doesn’t register where growth was happening in the Seattle area. The only way to determine whether centers are doing better than the rest of metro areas is to use a more geographically fine-grained measure than counties—which is something we did in our Surging City Center Jobs report.

So here are four takeaways:

- Don’t rely only county based data to make comparisons or draw conclusions about the health of city center job growth.

- Central counties are performing much more strongly in in the 2007-15 cycle than in the 2000-2007 cycle. Suburbs and smaller counties are performing worse than they did in the earlier cycle.

- The change in performance between these two cycles is indicative of structural change in economic growth patterns within urban areas: central areas are getting more growth (due to the expansion of professional and personal services and knowledge industries in the core); peripheral areas are performing worse than they did, especially during the housing bubble because they’re not buoyed by housing and sprawl.

- The within-cycle pattern of change (with central counties performing well late in the cycle) is consistent with the hypothesis that there has been a structural change in metropolitan employment growth patterns.

In a way this is a “half full, half empty” debate. Jed’s telling you the city center jobs glass is still half empty; we’re saying it’s half full—and that it was essentially empty in the last cycle (2000 to 2007). Not all job growth is happening in city centers—that’s not our point—but it seems clear that in this economic expansion, unlike the last one, large metro economies and central cities are leading the way. That’s an important development, in our view. Whether it continues and grows remains to be seen—and we look forward to exploring this question.