Except for boomers, we’re all less likely to be buying new cars today

One of the favorite “we’re-going-to-debunk-the-claims-about-millenials-being-different” story ideas that editors and reporters seem to love is pointing out that millennials are actually buying cars. Forget what you’ve heard about bike-riding, bus-loving, Uber-using twenty-somethings, we’re told, this younger generation loves its cars, even if they’re a bit slow realizing it. Using a combination of very aggregate sales data and usually an anecdote about the first car purchase by some long-time carless twenty-something, reporters pronounce that this new generation is actually just as enamored of car ownership as its predecessors.

The latest installments in this series appeared recently in Bloomberg and in the San Diego Union-Tribune. “Ride-sharing millennials found to crave car-ownership after all,” proclaimed Bloomberg’s headline. “Millennials enter the car market — carefully,” adds the San-Diego Union Tribune. San Diego’s anecdote is 32-year old Brian, buying a used Prius to drive for Uber; Bloomberg relates market research that shows that young car buyers especially like sporty little SUVs, like the Nissan Juke. Like other studies, Bloomberg relies on a vague reference to aggregate sales figures by generation: “Millennials bought more cars than GenXers,” we are told.

Earlier this year, and previously, in 2015, City Observatory addressed similar claims purporting to show that Millennials were becoming just as likely to buy cars as previous generations. Actually, it turns out that on a per-person basis, Millennials are about 29 percent less likely than those in Gen X to purchase a car. We also pointed out that several of these stories rested on comparing different sized birth year cohorts (a 17-year group of so-called Gen Y with an 11-year group of so-called Gen X). More generally though, we know that there’s a relationship between age and car-buying. Thirty-five-year-olds are much more likely to own and buy cars than 20-year-olds. So as Millennials age out of their teen years and age into their thirties, it’s hardly surprising that the number of Millennials who are car owners increases. But the real question is whether Millennials are buying as many cars as did previous generations at any particular point in their life-cycle.

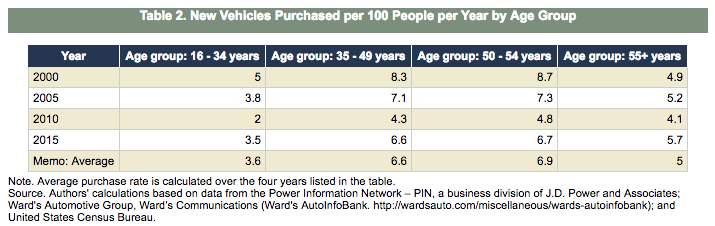

This is a question that economists at the Federal Reserve Bank turned their attention to in a study published this past June. Christopher Kurz, Geng Li, and Daniel Vine, used detailed data from JD Power and Associates to look at auto buying patterns over time, controlling for the age of car purchasers. (Their full study, “The Young and the Carless,” is available from the Federal Reserve Bank). Here’s their data showing the number of car purchases, per 100 persons in each of several different age groups.

These data show a number of key trends. First, the data confirm a pronounced life-cycle to car purchasing: those under 35 purchase very few new cars; car purchasing peaks in the 35 to 45 age group, and then declines for those over 55. Second, the state of the economy matters. Especially compared to 2000 and 2005, auto purchasing declined sharply for all age groups in 2010 (coinciding with the Great Recession) and has rebounded somewhat since then as the economy has recovered. Third, as of 2015, auto purchasing was lower for all age groups under 55 years of age than it was in either 2000 or 2005. Fourth, the big factor in driving car sales growth in the past decade was the over 55 group (increasingly swelled by the aging Baby Boom generation). Car sales for the over 55 crowd fell proportionately less during the great recession, and are at a new high (5.7 per 100 persons over 55). There’s clearly been an aging of the market for car ownership. The authors summarize this data as follows:

In summary, the average age of new vehicle buyers increased by almost 7 years between 2000 and 2015. Some of that increase reflected the aging of the overall population, but some of it reflected changes in buying patterns among people of different age groups. The most relevant changes in new vehicle-buying demographics over this period were a decline in the per-capita rate of new vehicle purchases for 35 to 54 year olds and an increase in the per-capita purchase rate for people over 55.

Kurz, Li and Vine look at the relationship between the decline in auto sales to these younger age groups and other economic and demographic factors. They find that declining sales are correlated with lower rates of marriage and lower incomes; that is to say: much of the decline in car purchasing among these younger adults can be explained statistically by the fact that un-married people and people with lower incomes are less likely to buy new vehicles, and as a group, there are relatively more un-married people and lower incomes among today’s young adults.

Their argument is essentially that if young adults today got married at the rate that they did in early generations, and if they earned as much as previous generations, that their car buying patterns would be statistically very similar to those observed historically. While the authors cite this as evidence that young adults taste for car-buying may not be much different that previous generations, in our view, this has to make some strong assumptions about the independence of later marriages and lower marriage rates and changed attitudes about car ownership. While those who do marry may exhibit the traditional affinity for car ownership, it may be that those who delay marriage (or who never marry) have different attitudes about cars. In addition, there’s growing evidence that the relative weakness of generational income growth may persist for some time, lowering the demand for car ownership.