More than half of workers in DuPage County, outside Chicago, say they’d like to get to work without a car. But nearly 90 percent of them drive anyway. What’s going on?

First, a little context.

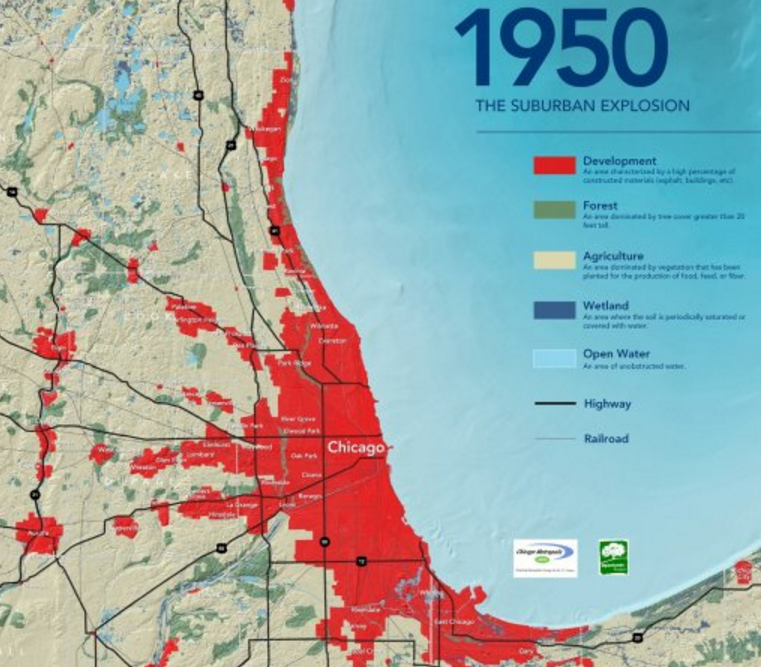

Your city probably has a DuPage County—if not by name, by profile. Beginning about 15 miles due west of Chicago’s Loop, DuPage boomed in the last several decades of the 20th century, filling the spaces in between 19th century railroad suburbs with low-density subdivisions and office parks, and growing from just 150,000 people in 1950 to nearly a million in 2010. Today, it’s home to a disproportionately affluent slice of the region (median household income is $80,000, as compared to just over $60,000 for the metro area), as well as some of the Chicago region’s largest employment centers outside of downtown, including Fortune 500 companies like Ace Hardware and (for the moment, anyway) McDonald’s.

In other words, DuPage County is more or less a poster child for affluent, “successful” postwar sprawl. That said, its relative economic position to Chicago’s core has been declining recently, as a result both of the growing job base and high-income population of the center city and the growing ethnic and economic diversity of DuPage itself. Thus the poll of DuPage workers, commissioned by the county’s economic development arm, to see what the county might do to attract and keep jobs from fleeing to downtown Chicago or elsewhere.

So why don’t people who say they’d like to take transit actually do it?

It’s not that DuPage doesn’t have transit services. It’s actually pretty transit-rich for suburban America: three Metra commuter rail lines, with 26 stations, pass through the county; a handful of bus lines also criss-cross the area.

But for those transit services to be useful for commuting, they have to actually go where people are going—their homes and jobs. And a closer look shows that they don’t.

Back in 1950, development in DuPage County was focused around the commuter rail lines. If you lived in DuPage, you probably lived within a relatively short distance of rail transit—which gave you access not just to the city, but to every other community on your line.

Since then, however, planners and developers assumed that virtually everyone would use a car to get around, and so the overwhelming majority of the hundreds of thousands of jobs and homes that DuPage County has added in the last several decades have been built too far from rail stations to be accessible. Instead, they’ve been focused along highways and wide arterials built with little to no consideration of transit, walking, or biking.

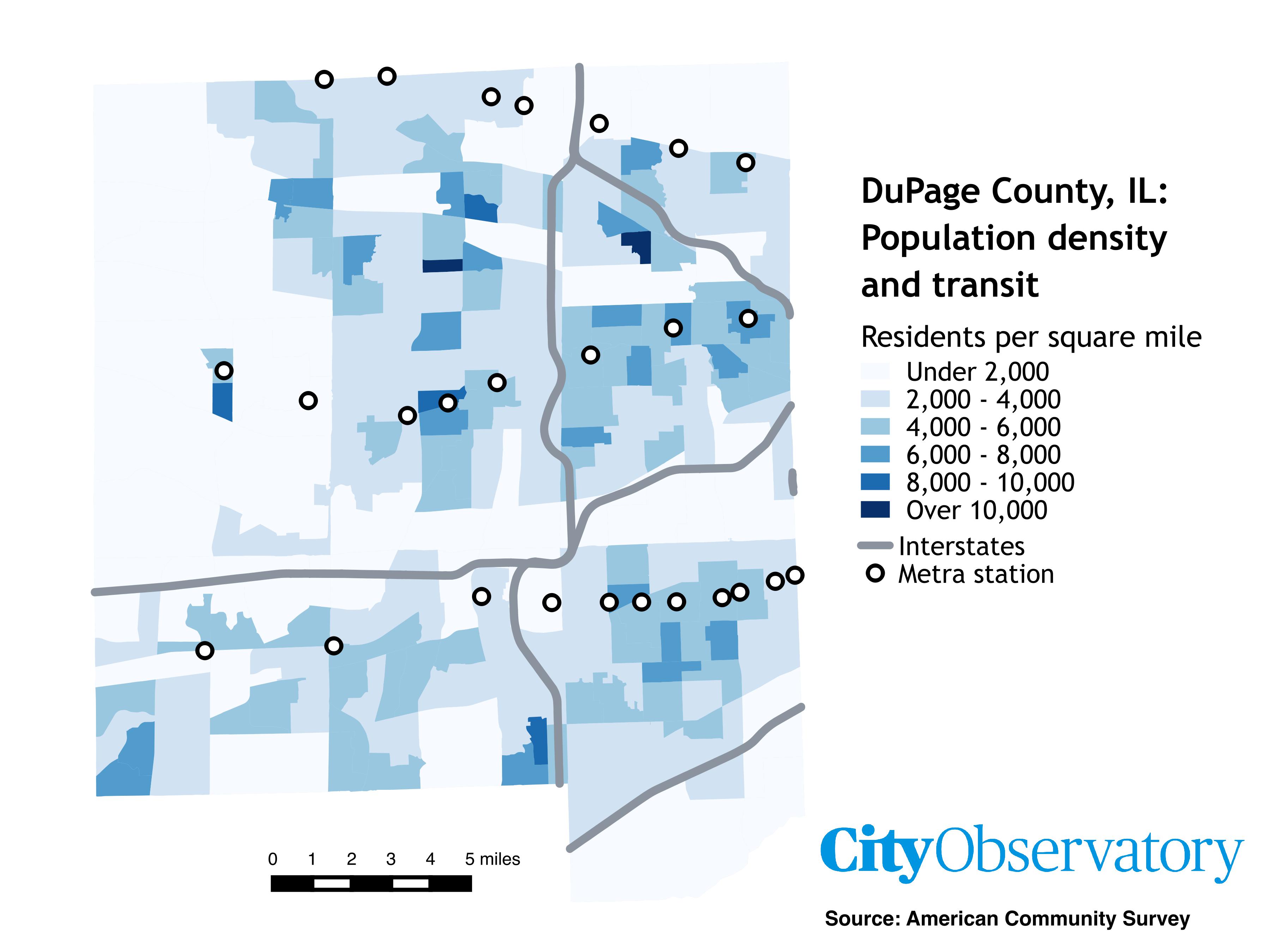

We can see the effects easily in maps. A population density map of DuPage County shows that there’s no strong correlation between where people live and where Metra stations (the white circles) are.

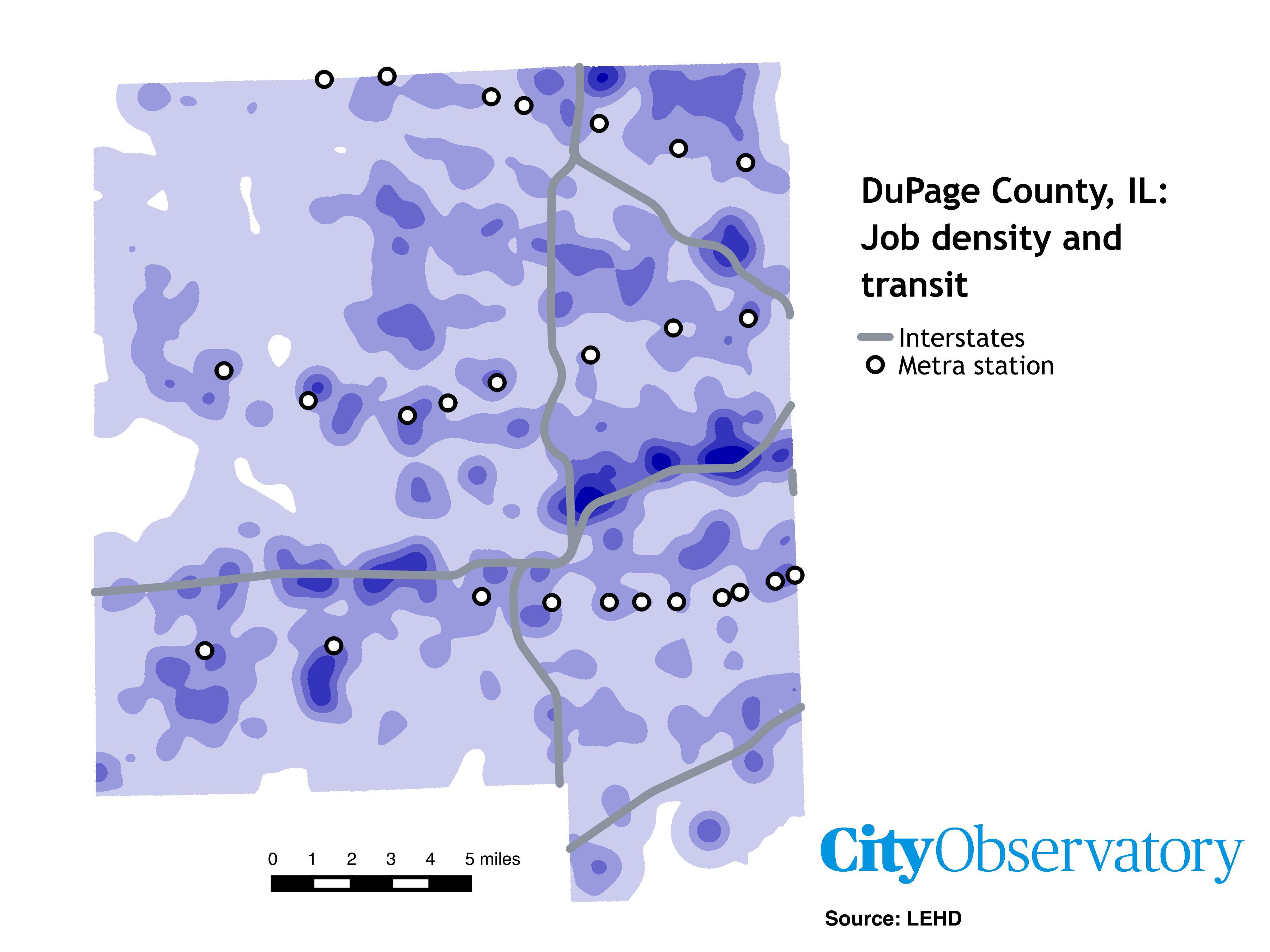

But as we’ve discussed before, destination density is perhaps an even more important factor in determining how someone gets to work. Unfortunately, a heatmap of DuPage County jobs looks even worse in terms of rail access:

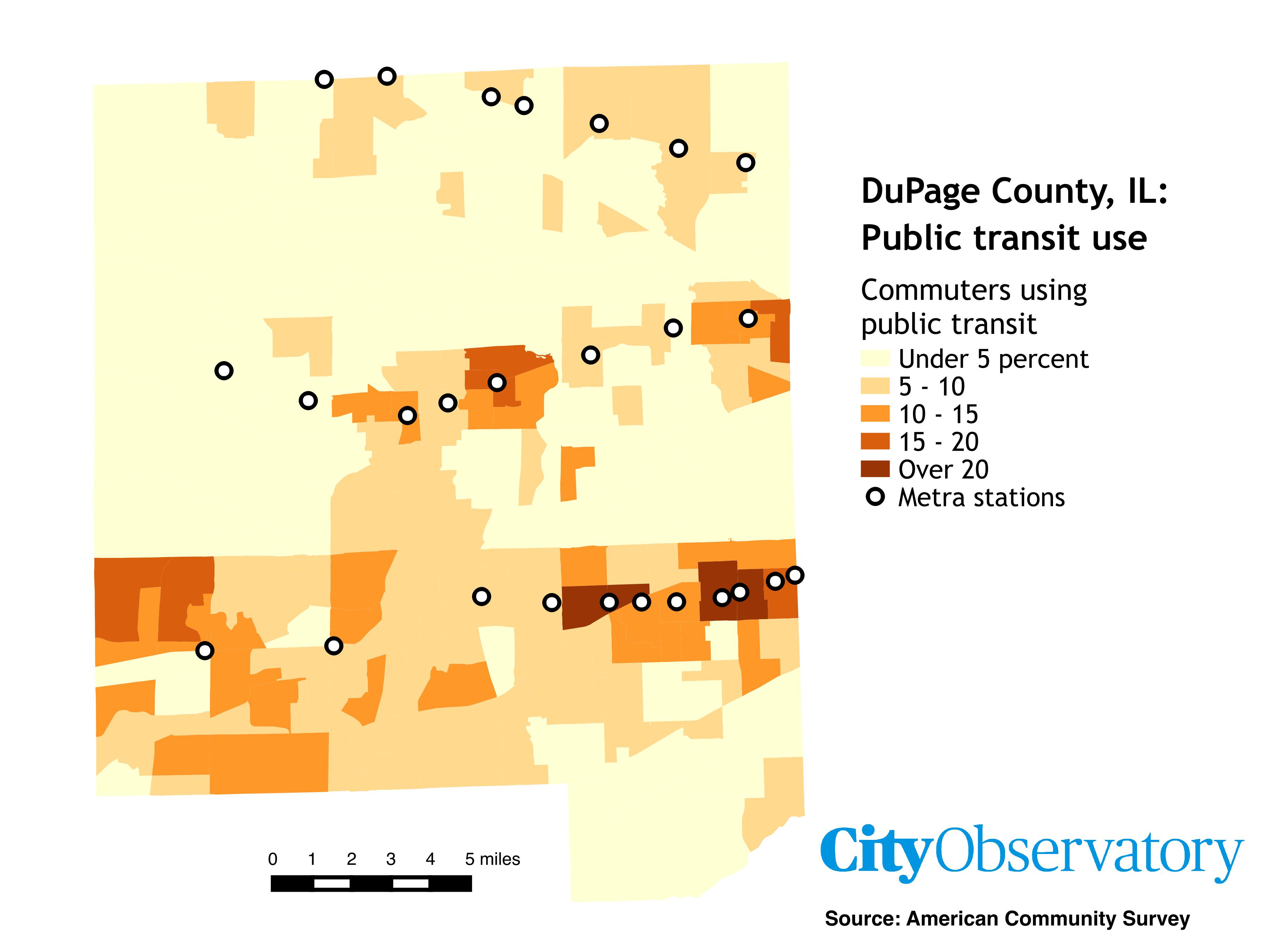

Nor does the bus network help that much. For one thing, the spread-out nature of development means that no one bus line can have easy access to many homes or businesses either—and even someone who steps out of a bus relatively close to their destination has to navigate roads and parking lots that aren’t designed for walking. Partly as a result, the buses simply don’t come that often: at best, every 15 minutes at rush hour, which may be on the edge of acceptability for show-up-and-go service in the afternoon or late in the evening, but is a burden for someone who really needs to be on time for a job. Other buses come much less frequently, even at rush hour.

This is where you wait for the bus in the jobs-rich I-88 corridor in DuPage.

So someone who wanted to commute to their job in DuPage County by transit would discover 26 rail stations which are probably within walking distance of neither their home nor their job, and a network of buses that aren’t much better, most of which come too infrequently to be reliable for very time-sensitive trips like a commute, and which require getting to and from stops that are located on roads that are hostile or dangerous for walking.

In other words, the decisions of planners and developers over the last several decades have created a land use pattern that essentially locks in transportation choices for all future residents, who are now stuck commuting in ways they say they’d rather not. And DuPage, like other car-dependent suburbs around the country, may be losing some of its economic base as a result.

One response to this, of course, is that for most of the 20th century, car-dependent development is what people wanted. If people wanted to live or work near transit stations, then developers would have built homes and offices there. Which: maybe! But if that’s the case, then it’s odd that basically every municipality in DuPage County has taken the step of legally restricting developers from doing so. Nearly every suburb prohibits apartments, offices, and most other space-efficient commercial uses outside a radius of just two or three blocks from their train station. And even within that radius, density is restricted and discouraged with parking requirements and other rules.

And, of course, over the decades, the federal, state, and local governments have invested billions of dollars in highways and road widening, without which most of the development of the last half-century would have been impossible. The size and nature of the public investment prompted a complementary set of private investments that was utterly, and in some ways irrevocably, dependent on auto travel. In fact, nearly the only people who do commute to work by public transit in DuPage are the ones living near Metra stations.

The point is not that, absent these policies, there would have been no new subdivisions far from transit. Nor is it that the right outcome would be for every Metra station to be a little mini-Loop.

Rather, these policies exist on a spectrum—a sliding scale of how many people and jobs will be within walking distance of high-quality transit, on streets amenable to traveling on outside of a car—and we happen to have chosen one extreme, with the result that 90 percent of people drive to work. Including, at a minimum, four out of five people who say they’d prefer not to.

The problem with that isn’t just that some of those urban Millennials aren’t enjoying their preferred lifestyle. It’s that hundreds of thousands of people—including people of modest means—are forced to pay thousands of dollars more in transportation costs every year. And that people who really can’t drive, because they can’t pay for the costs of owning a car, or because they’re too young or old or have some physical disability, are shut out of full participation in society, or forced to waste hours of their days on inefficient transit.

These outcomes, as a result of changing land use patterns, take decades to unfold, and neither DuPage nor the rest of the Chicago region—which looks pretty similar, outside downtown—is going to slide the scale back towards a more balanced transportation system immediately. But lots of little decisions add up.