Its apparent to almost everyone that the US has a growing housing affordability problem. And its generating more public attention and public policy discussions. Recent proposals to address housing affordability in California by Governor Jerry Brown and in New York, by Mayor Bill de Blasio have stumbled in the face of local opposition. Its a delicate moment in housing policy debates.

So now we’re being told, by our very smart friends at the Sightline Institute, that we ought not to talk about urban housing problems using the terms “supply and demand.” Excuse us if we politely, if firmly–and wonkily–choose to disagree. Housing affordability problems, in Seattle, San Francisco, and just about everywhere have everything to do with supply and demand.

OK, sure: for general audiences, saying supply and demand may cause some people’s eyes to glaze over, and for others, it may be taken as a sure sign that one has succumbed to a heartless neo-liberal paradigm. For many people, we know, any mention of economics reminds them of a painfully unpleasant under-graduate course. And Sightline has prudent advice about how to talk about the problem in the media. They say:

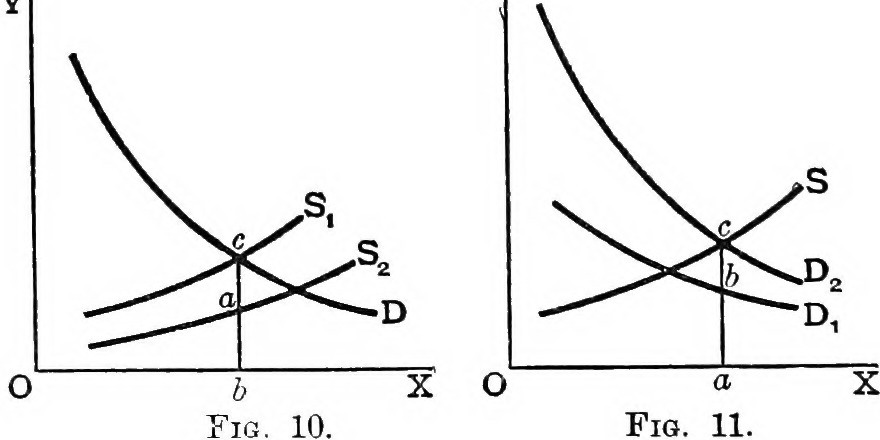

But for us at City Observatory, this is a teachable moment. The demand for cities and for great urban neighborhoods is exploding. Americans of all ages, but especially well-educated young adults are increasingly choosing to live in cities. And in the face of that demand, our ability to build more such neighborhoods and to expand housing in the ones that we already have is profoundly limited, both by the relative slowness of housing construction (relative to demand changes), and also because of misguided public policies that constrain our ability to build housing in the places where people most want to live, to the point in many communities, we’ve simply made it illegal to build the dense, mixed-use, walkable neighborhoods that widely regarded as the most desirable.

Our key urban problems–housing affordability, concentrated poverty, gentrification, long commutes–are all either directly caused or significantly worsened by this imbalance between housing supply and demand.

But there’s a studied disbelief in many media outlets that market forces have anything to do with housing. NIMBY’s believe that blocking new construction will keep prices down, when the opposite is true. As a result, we paradoxically pursue strategies that make housing affordability problems worse.

Two recent bits of evidence remind us that supply and demand are very much at work. A terrific analysis, written by Financial Times reporter Robin Harding and echoed by Vox’s Matthew Yglesias shows how even in a big dense city, increasing supply to meet demand keeps prices in check. In Tokyo, one of the world’s largest and densest metropolises, housing prices have barely budged in the past two decades, because Japan makes it relatively easy to build new housing. Local jurisdictions and neighbors don’t have effective veto power over new development, so when demand increases, supply responds relatively rapidly, and as a result house prices remain much more affordable.

Closer to home, Yardi Matrix is a real estate data research firm tracks and regularly reports on changes in rents and housing occupancy in major markets around the nation. They’ve noted nearly 300,000 new apartments will be completed this year. As a result, in many markets supply is finally catching up to demand, and rental price inflation is going down in places like San Francisco, Denver, Austin and Houston. For example, after seeing double digit growth in rents for several years, rents in San Francisco are up just 3.5 percent in the last 12 months, according to Yardi. In some places, such as the oil patch, where demand has declined due to layoffs in the energy sector, rental prices have actually declined.

While these trends are hopeful signs, and while they clearly illustrate that the market forces of supply and demand are very much at work, there’s still much to be done to re-work our public policies to address affordability, urban livability and equity. We don’t expect the demand for urban living to abate any time soon–in fact, there’s good reason to believe that it will continue to increase. And it’s still the case that we have a raft of public policies – from restrictions on apartment construction and density, to limits on mixed use development, to onerous parking requirements, and discretionary, hyper-local approval processes – that make it hugely difficult to build new housing in the places where it’s most needed.

Many of the problems we encounter in the housing market are a product of self-inflicted wounds that are based on naive and contradictory ideas about how the world works. We believe that housing should both be affordable and a great investment (which is an impossible contradiction), and we tend to think the laws of supply and demand somehow don’t apply to one of the biggest sectors of the economy (housing). At their root, our housing problems–and their solutions–are about understanding the economics at work here. So in our view, it’s definitely time to talk about supply and demand.