At his blog, The Transport Politic, Yonah Freemark pushed back this week on the idea that we’re seeing a revolution in the way people get around cities and suburbs, largely thanks to new transit-and-bike-friendly Millennials.

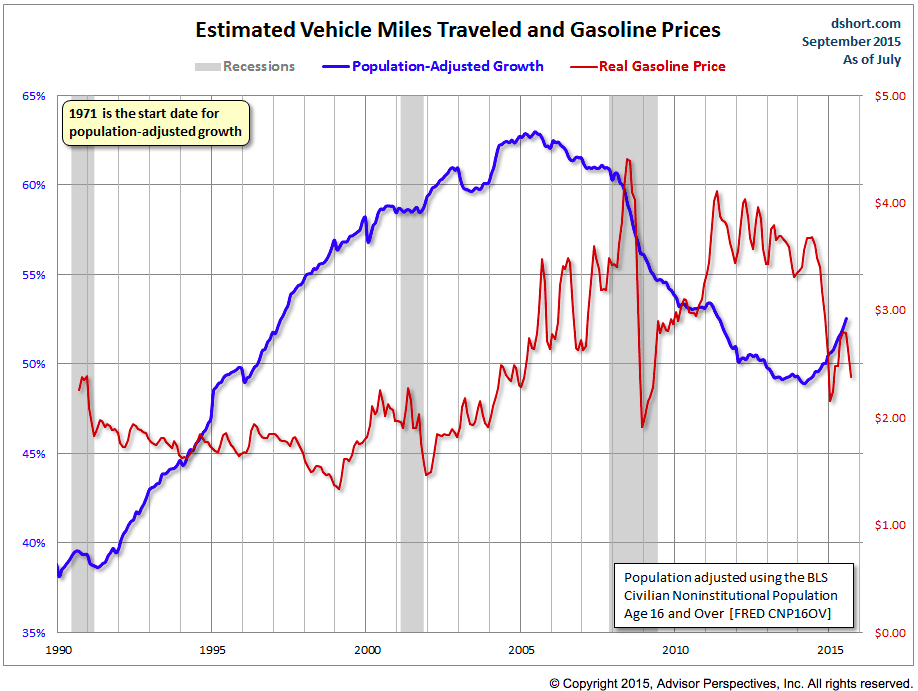

In fact, he cites one of our posts as an example of a narrative he doesn’t think is quite right: that despite an uptick in driving as a result of dramatically cheaper gas prices, economic and preference-based fundamentals suggest that we are still in the midst of a historic decline in driving after generations of consistently rising car dependence.

Freemark, who also works at Chicago’s Metropolitan Planning Council, is an excellent commentator on transportation and urban development, and we are all very much on the same page in believing in diverse, inclusive cities whose transportation systems contribute to walkable, integrated, sustainable neighborhoods.

Moreover, the central point of his post is not just correct, but hugely important for all transit advocates and urbanists to understand. As we’ve written, changing preferences are not enough to change transportation behavior, because a person’s behavior heavily depends on their options. Those options, in turn, depend on available transit services and land use patterns. If the only available public transit is a very slow bus that comes once every 30 minutes—or the only bike route is along a high-speed stroad without a bike lane—it’s likely that even the most car-hating Millennial will get behind the wheel to get to work. Land use is similarly important: if your job isn’t anywhere near a transit station, it’s extremely unlikely you’ll be able to avoid driving, even if you’d really like to. In effect, land use patterns lock in place the mode choice preferences of previous generations and changes in behavior can happen only slowly. We can’t have a transportation revolution without major improvements to transit services and road design, and major reforms to our land use laws.

(Another big part of transportation equation is transportation prices—which include gas prices, but also policy-driven pricing of scarce road space, parking, and insurance. In many cases, pricing may be one of the best and easiest ways to remove some of the subsidies we’ve given to private vehicle travel.)

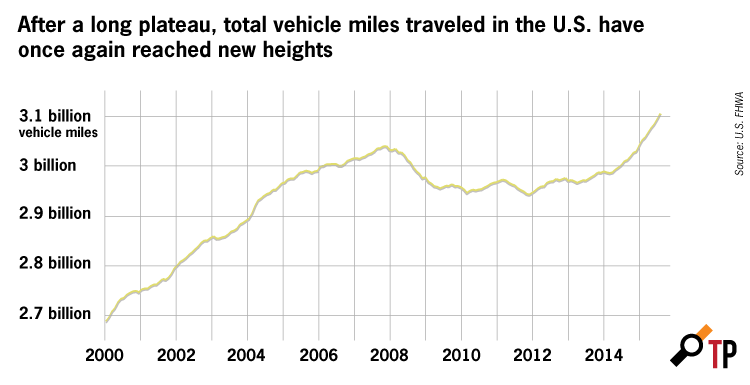

But despite all that, there is more progress than Freemark allows. He shows, accurately enough, that total vehicle miles have hit a new record after a dip during the Great Recession. But population growth is doing most of the work there: per capita vehicle miles are still far below their 2005 peak, and while there has been a small rebound corresponding to the fall in gas prices, the pattern appears to remain consistent with a long-term slowdown in driving.

It’s also extremely encouraging that, as we reported in Surging City Center Job Growth, employment is re-concentrating in downtowns after decades of decentralization. Even without major changes in residential patterns, increasing the destination density of relatively well-served central areas can represent a major improvement in non-car transportation options, allowing the growing number of those who are so inclined to use transit.

In addition, while available transit services and land use patterns limit the extent to which changing preferences can be translated into behavior, the flip side of that dynamic is that the modest changes in behavior we’ve seen so far mask a truly massive change in preferences. We can observe those preferences in urban real estate, where indicators like “the Dow of cities” reflect the increasing demand to live in relatively central locations, and other researchers like those at Walk Score show that people are increasingly willing to pay a premium to live in walkable, transit-served neighborhoods.

Freemark is right to suggest that our biggest challenges are political: how to convince decision-makers to invest in transit services and reform our streetscapes and land use laws to make transit, biking, and walking a viable option for those who would like to use them. But those changing preferences themselves constitute major political leverage. Localities in the position to allow more walkable, transit-served development are likely to reap the benefits of greater housing demand by satisfying some of our “shortage of cities.” In that sense, much of our work as urbanists should be about illuminating the connections between street design, transit service, and land use law—connections that are still far from well understood by many civic leaders and their constituents—and showing what kinds of changes can create the communities people envision for themselves.

But it’s also true that focusing only on changing preferences sometimes leads transit advocates to put less emphasis on what Freemark calls “an ideological claim” about why creating cities where transit, biking, and walking are viable options is a better choice for everyone. Different people will have different priorities, of course, but two of the central advantages of transportation networks that don’t depend entirely on private cars have to do with inclusion and environmental sustainability. Allowing people to go without a car—or to use it less than they might otherwise have to—can save low-income households thousands of dollars a year, money that would be much better spent on school supplies, food, clothes, or almost anything other than gasoline, insurance, and car payments. Removing a neighborhood’s total dependence on automobiles also allows people who are too young or old to drive, or who have a physical disability that makes it difficult to drive, to remain independently mobile. And transit can dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions, not only through directly displacing polluting car trips with more emissions-efficient (or zero-emissions) travel modes, but by allowing cities to be built more compactly.

The car dependence of American cities today is the result of nearly a century of interventions, both dramatic and subtle, into the urban fabric. Reversing that work is a project of a similar scale. But there has been some progress. More importantly, changing preferences give us reason to believe that there is the will to make much more; and our understanding of the central role of transportation in equitable, sustainable cities gives us the mandate to pursue that progress. Millennials aren’t going to save our cities single-handedly any time soon, but they’re helping us move in the right direction.